2020 has been a year like no other, in particular as a result of the Black Lives Matter movement in the US and its subsequent impact on race issues globally. Toni Pyke unpacks the moment and presents an educator’s guide, having witnessed the realities of racial segregation in South Africa.

“… But if you only have love for your own race

Then you only leave space to discriminate

And to discriminate only generates hate

And when you hate then you’re bound to get irate, yeah…

…Wrong information always shown by the media

Negative images, is the main criteria

Infecting the young minds faster than bacteria

Kids wanna act like what they see in the cinemas

Yo’, whatever happened to the values of humanity

Whatever happened to the fairness and equality

Instead in spreading love we’re spreading animosity

Lack of understanding, leading us away from unity…”

For those who may not know, the above lyrics are from the 2003 single by American hip-hop band Black Eyed Peas “Where is the Love”, watched more than 615 million times on YouTube. I’ve listened to this single so many times over the last 17 years and it has the same poignancy today, perhaps more so, as it did back then, in a world gone “insane” (Black Eyed Peas full lyrics).

Over the years I have tried to make sense of this, and since living in South Africa and witnessing the realities of racial segregation, I have begun to appreciate the enormity of the injustice and pain of racial inequality.

Racism is not unique to any one country.

While many of us are acutely aware of the experiences and incidences of racism in the US, a recent survey conducted by the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights among 12 EU states reported that Ireland is among 3 countries (along with Austria and Finland) in the EU with the worst records of racism based on the colour of someone’s skin. The EU-MIDIS II 2018 survey shows that Ireland had some of the highest rates of hate-motivated harassment, 51 per cent compared to the average of 30 per cent across the 12 countries surveyed.

On May 25th this year, the graphic reality of racism was demonstrated through the violent and fatal arrest of George Floyd, an unarmed black man, by Minneapolis police in the US. While police racial profiling and brutality in the US is commonplace, Floyd’s murder, which was captured on video in its entirety and went viral across social and mainstream media, was the last straw for many Americans. This, and the many other documented public killings by police officers is a symptom of the systematic racism, inequality and injustice that ‘black’ Americans experience on a daily basis, what one US lawyer termed a “pandemic of racism and discrimination”. This means that racism today is commonplace and is experienced in all aspects of society.

George Floyd has become a symbol of the struggle for racial equality, reigniting and intensifying the ongoing debate surrounding the racism and injustice that ‘black people’ constantly endure. It has also revived the age-old question of the slave trade and slavery, along with the historical implications for those countries who engaged in and benefitted from it.

Following Floyd’s death a wave of protests and demonstrations took place across the US and quickly spread throughout the world, in a show of solidarity, and to expose the globalised nature of racism and inequality. While a few demonstrations have included incidences of violence and looting, the majority of the protests throughout the world have been peaceful. In Ireland, peaceful demonstrations took place in Galway, Limerick, Belfast and outside the US Embassy in Dublin, supporting the #BlackLivesMatter movement and raising awareness of the realities of racism faced by asylum seekers in this country and in particular the controversy surrounding direct provision.

At a protest in Bristol, UK the statue of Edward Colston, a key beneficiary of the UK’s role in slavery, was toppled and thrown into Bristol Harbour. There have been similar calls for the removal of statues of imperialists, racists and colonisers, such as at the University of Oxford, UK where the removal of the historic statue of Cecil Rhodes has been long debated (see BBC why Cecil Rhodes is a central figure in Africa).

The obsession with embodying individuals who personify the violence of colonialism and slavery is represented – and opposed – across the world. In 2015, for example, university students throughout South Africa protested against a statue of Cecil Rhodes in Capetown through the #Rhodes Must Fall campaign highlighting and challenging the continuing oppression, social and economic segregation and racism of black populations.

An example of systematic racial oppression and inequality

Race politics has defined South Africa in the past and continues to challenge it in the present.

In a post-WW2 era where the rest of the world sought to consolidate and protect global human rights through the UN Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the newly elected National Party in South Africa, authorised and forcefully enforced the legal segregation of ‘black’ people from ‘white’ people (along with various other official categories of colour and bizarre attempts at officiating these) in all spheres of life, institutionalising ‘white supremacy’ through a system called ‘apartheid’. The government spent the next 5 decades devising various violent political and legal strategies to subjugate and oppress an entire race of people, primarily based on the colour of their skin.

The seeds of racial oppression, however, were sown in South Africa long before 1948. Apartheid codified what had already been normalised. Way back in the 1700s when Europeans were in a hurry to find the fastest trade route to India, they happened upon South Africa, which began the historic ‘scramble for Africa’ and the establishment of European colonial empires (the exploration, conquering and settling of Europeans in ‘colonies’), which were facilitated by the global trade in human beings as slaves who were critical in supporting the modern world of capitalism that many of us benefit from today. This history has been instrumental in the institutionalising of racial oppression across all sectors including for example the ways that ‘white’ people continue to have preferential access to financial services, the criminal justice system, employment opportunities, housing, healthcare, education, politics, media, entertainment, development, etc.

Academic research and writing around this time presented a biological case for the superiority of the ‘white race’ over those considered ‘non-white’. Such ideas gained serious political traction in America and in particular in the southern states, where black slaves in general had no social, legal, political, economic or human rights. Therefore, systems in the West and in the colonies were developed by and for white populations, which over time have been violently defended, protected and sustained. As we see most glaringly in the US today, despite the abolition of slavery and the various attempts to enshrine and enforce black civil rights, these continue to evade the majority of ‘black’ people (see The LBS team, 12 June 2020).

The scandal, atrocities and long-term consequences of the colonial slave trade over the centuries, are a painful reality to discover. It is not only an episode in our ruthless past, but its repercussions remain a reality of the world that we all live in today. As painful as it is to acknowledge, “This is a history which we have all been shaped by, albeit unequally: understanding that is a responsibility for all of us so that we may do things differently”.

The debate about slavery of the past, must include the modern day slavery that we continue to endorse – for example through forced labour, child labour or slavery, child soldiers, child marriage, bonded labour, human trafficking etc. The devices we use, the clothes we wear, the food we eat, the rubbish we throw away, and so much more, continues to connect us to the individuals and communities who are enslaved throughout the world.

Rhodes (and all that he represents) Must Indeed Fall – but how?

The clip above is from the brilliant, animated movie A Bug’s Life, released in 1998. The movie plot is about “A misfit ant, looking for “warriors” to save his colony from greedy grasshoppers, recruits a group of bugs that turn out to be an inept circus troupe”.

But it’s about way more than this.

Flik, a young ant in the colony, challenges the authority of the grasshopper gang leader and the gang in general for their bullying tactics in demanding and taking their food supplies and leaving them with insufficient supply for themselves for the winter. Now, imagine that the ants are ‘non-white’ and the grasshoppers are ‘white’.

In the clip above, in less than 2 minutes, Hopper – the grasshopper gang leader – explains why grasshoppers (white supremacists) need to sustain their control over the ants – “…It’s not about food – it’s about keeping those ants in line..”. Hopper fears a revolution – if one ant stands up, then they all might, which may impact on their ‘way of life’!

A challenge to the lifestyle and status of those in dominant positions within our societies is a key ingredient of white supremacy.

“Education is the most powerful weapon to change the world”

The above quote is from Nelson Mandela, the first black president of South Africa. Mandela spent his whole life challenging racism and inequality in South Africa until his death on December 5th, 2013 at the age of 95 years.

The day after Mandela’s death in 2013, I was attending a local Sunday Mass. During the homily, the priest made note of Mandela’s passing and then launched into a character attack of Mandela’s role in challenging the dogmatic suppression and oppression of an entire race, reminding us that Mandela was in fact, a “terrorist”. The priest was referring to Mandela’s short lived active participation in the military wing of the political party the African National Congress (ANC), uMkhonto we Sizwe – The spear of the nation, formed in 1961 after many decades of peaceful protest.

A year later Mandela was arrested, tried and sent to prison for 27 years on charges of treason against the apartheid state. In 1994 elected as the first black president, he sought to bring freedom and peace for all South African citizens, black and white, and enshrine these rights in one of the most inclusive government Constitutions in modern history (see the Bill of Rights here).

The most significant contribution of Nelson Mandela’s life and the critical importance and relevance to our continuing struggle for ‘freedom’ and ‘equality’ in its widest sense – is the legacy that he has left behind. His wisdom, experience, teachings, compassion, lessons and reflections – in a nutshell, the life that he lived, including the years he spent in prison to challenge the gross inequalities of racial segregation.

The comments made during that homily demonstrate the normalising of racial inequalities and the limited challenges by the wider society to the entrenched racial prejudice that we still need to contest and set straight.

For Mandela education is key to this change.

While tearing down of statues, renaming street signs, returning museum artifacts, etc., will help with the healing of the hurt from the past, it is the structural changes in the systems that we take for granted that must radically change. Yet, at the same time, we must not forget history. It should not be erased and should serve as a reminder of a past where we never want to return.

Where can I find out more?

There are thousands of videos, movies, books, social and mass media opinions, statements, debates, lectures, community groups, and so on about the issue of racial inequality and what we can do to respond and take action on this – and many other issues of injustice. It’s difficult to know where to begin.

The following resources further explore the issue race, racism and race inequality:

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

Firstly, what is “racial discrimination”? The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination provides us with a clear definition of a legal understanding of the term ‘racial discrimination’, outlined in terms of ‘freedoms’ of human rights ‘on an equal footing’:

“… any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life”.

It is important to know that there are legal systems in place that seek to keep a check on the injustices of racism throughout the world. One such structure is within the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination which independently monitors if and how the state parties (those countries who signed up to the convention – currently 182) implement the 1965 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD).

States parties are expected to submit regular reports (see here for individual country reports) to the Committee showing how they are implementing the Convention in their country (initially in the first year of signing and then every 2 years). Based on their findings, the Committee provides ‘concluding observations’ (see here for a listing of these) which addresses concerns and provides recommendations to the State party on areas of alignment and improvement in implementing CERD (Check out the latest report by the Committee and supplementing NGO reports on Ireland’s alignment with CERD ).

- Challenging our perspectives on race and racism: Individually, we need to look into ourselves and understand our own position within the debate and how best we can respond. Take a look at the video that presents the views of young people in Ireland that presents “What does “Irishness” look like?

- Educate Together have a collection brilliant resources on their website focused on exploring, learning and teaching about anti-racism in schools, beginning with a focus on exploring and realising our own ‘privilege’ and prejudice and working towards challenging them in the school and classroom practice.

- 9 tips teachers can use when talking about racism – has some great videos and ideas on supporting young people in challenging racism.

- The Irish Network Against Racism has some good points of reflection in approaching and challenging racism in Ireland, including 10 things you can do about racism in Ireland; defining what racism and inequality is and what it looks like in Ireland today.

- Civil rights activist and educator Deray Mckesson has outlined 8 ways that we can support the struggle for racial justice and transform into a more inclusive society. Key to impacting on this change is to listen to understand, engage in informed debate, take appropriate action. See his perspective on “How you can be an ally in the fight for racial justice” here.

- Support: the struggle for race equality aligned through the #BlackLivesMatter movement, who seek to highlight the issues of systemic and endemic racism throughout every fabric of our societies.

- Consider history and the issue of colonial slavery and calls for reparation: An example of reparation for slavery of the past is the Centre for the Study of British Slave-ownership at University College London who are involved in an interesting project that tracks and documents how “Colonial slavery shaped modern Britain and [how] we all still live with its legacies”. The project names prominent people, institutions and business who were involved in “the [colonial] slavery business” (also check out the fascinating Legacies of British Slave-ownership database), and challenge us all to “explore and understand the past in order to address the ways in which injustices may be acknowledged and set right”. A key success of the project is that major British institutions such as the Bank of England and Lloyds of London among others, have recently acknowledged their links with the slave trade, slavery and the British empire and are preparing to provide money to redress the inequalities of the past and to be more inclusive in their business operations in the future.

- There are also some interesting resources (although US focused) on the Center for Racial Justice in Education website.

Book recommendations

- Nelson Mandela: The Long Walk to Freedom

- To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, (and the 1962 movie of the same name) which highlights the ugly injustice of racism in segregated America as seen through the eyes of Scout Finch whose father, attorney Atticus Finch, attempts to represent a black man who has been unjustly accused of rape

- See also some good book recommendations on the theme of anti-racism in the NY Times.

Watch these 4 TED videos

How to deconstruct racism one headline at a time – TED talk by Baratunde Thurston who explores racial prejudice in ‘white’ American and demonstrates the power of language to change stories of trauma into stories of healing — while challenging us all to ‘level up’.

The Danger of a Single Story. Our lives, our cultures, are composed of many overlapping stories. Novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie tells the story of how she found her authentic cultural voice — and warns that if we hear only a single story about another person or country, we risk a critical misunderstanding

We need to talk around an injustice – TED talk by human rights lawyer Byran Stevenson (of the Just Mercy movie) about the US (in)justice system and the gross inequalities surrounding this.

What do we mean by systemic Racism? – by artist Paul Rucker who looks at the legacy of systemic racism in the United States through art and artifacts connected to the history of slavery — from branding irons and shackles to postcards depicting lynchings (Warning: there are some graphic images in this talk).

Explore more on developmenteducation.ie

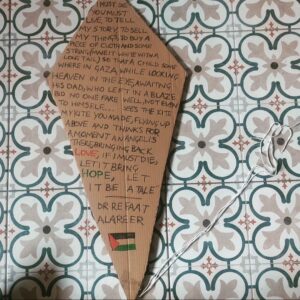

Urgently needed and timely new resource from Afri

Ciara Regan reviews Afri’s latest resource, Sowing Seeds of Peace, for post primary teachers which is adaptable and immediately useful across a range of school subjects.

It’s international women’s day. Don’t forget to tag us now that you feel #prettypowerful

From getting out to vote and entertaining two children off school due to it being a make-shift polling station, Ciara Regan reflects on international women’s day 2024.

Punching above its weight

Juan Acevedo-Ossa explores South Africa’s case against Israel as the latest example of its ability to act as a normative superpower, exceeding the great powers in shaping global moral discourse.

Empathy in a Divided World – workshop

Join us for this online session Empathy in a Divided World led by Brighid Golden to discuss how educators can respond to the challenges of selective empathy, both for ourselves personally and with others in our different settings.

What does Palestine have to do with Africa?

How does Israel’s current aggression on Gaza relate to Africa’s own history of political violence in Uganda and Africa?

‘What life is this?’: Escaping Ukraine’s occupied territories

From food shortages to informants, eight evacuees talk about life in Russian-occupied towns