Who we are

Areej Khan and other Saudi women.

What we did & how we did it

Although there is no legislation against women driving in Saudi Arabia, a fatwa (moral law) against public “gender mixing” prohibits it. The fatwa is enforced by the country’s morality police, the muttaween. Women (often carrying foreign driving licences) caught driving are taken to a police station, usually with their father or brother, to sign a pledge never to drive again.

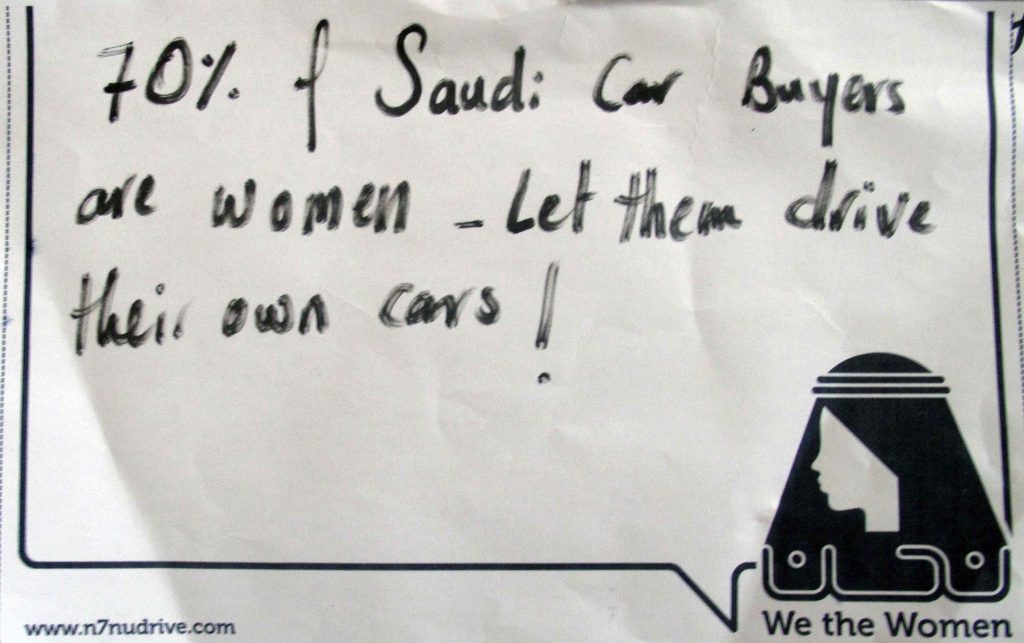

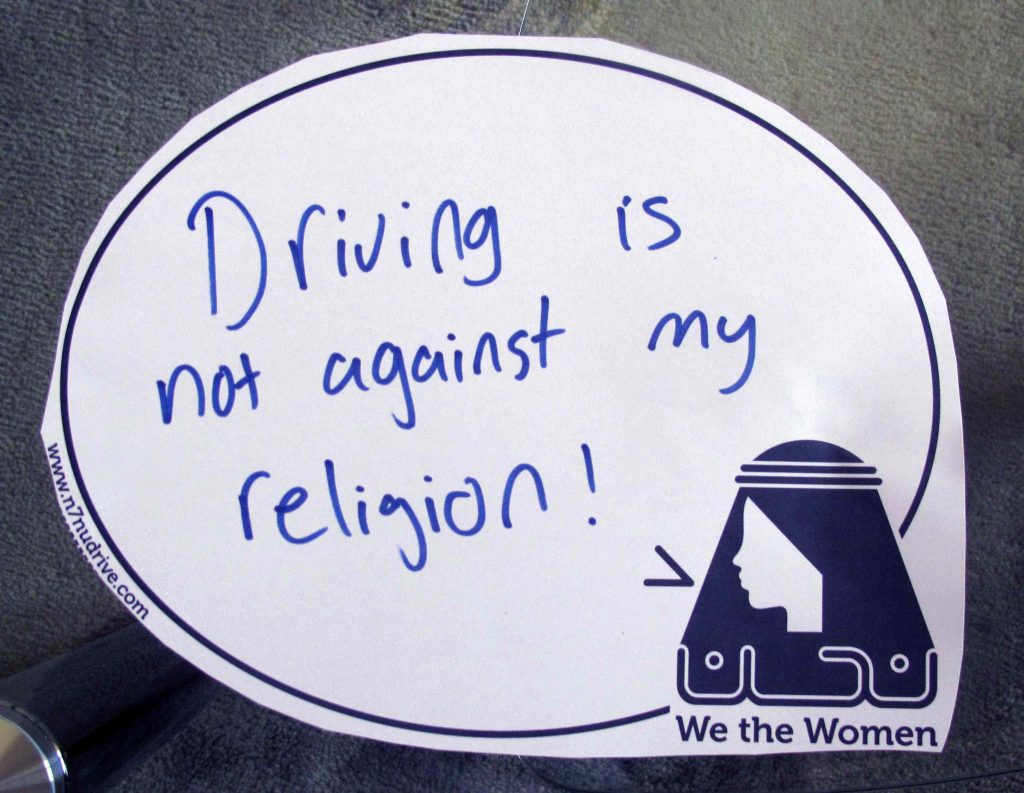

In 2009, to generate social dialogue on the ban among Saudi citizens, a Saudi artist and graphic designer living in the US created a low-budget online and offline campaign called ‘We the Women’. Adapting the thesis she had produced while studying at the School of Visual Culture in New York, Areej Khan designed a set of “declaration bubble” stickers and encouraged people to print them out, fill in their thoughts, and then distribute them in public spaces — including on cars. Supporters were also encouraged to photograph their personalised stickers and upload them to the N7nu – We the Women’s Flickr set or Facebook page, or to email them to Khan anonymously.

Was it successful?

The Facebook page was central to the campaign, becoming a central point of discussion on the issue of women driving. “Most of the people participating on the Facebook page are against women driving,” said Khan. “There’s back and forth and debate on the group. I had to be prepared [for the fact that] I can’t control what this is at the end. It’s about finding a solution as a community, not what I think or am attached to.”

The success and reach of the campaign was driven mainly by the people in Saudi Arabia who downloaded stickers and expressed their thoughts on the issue. By focusing on a question — “to drive or not to drive” — rather than a static message about women’s rights, the campaign opened itself up to the participation of a much wider audience (both those for and against women driving). This prevented the campaign from being cast off as the product of just another westernised, expat Saudi woman, and generated some healthy controversy and international media attention.

At the time, Khan said that although the project received many comments opposing women driving in Saudi Arabia, “a lot of people say they think that will change soon, because of the voice given to women by projects like this.”

- the #women2drive campaign, initiated two years later in 2011, renewed public interest and actions that women in Saudi Arabia could participate in directly.

- the campaign reached its peak on June 17 2013 when several women who had sat behind the wheel on the country’s roads filmed themselves as a stunt to normalise the experience of women driving, were briefly arrested by police.

- this included IT consultant Manal Al Sharif who was arrested following posting a video of herself and Wajeha al-Huwaider, a women’s rights activist, driving around and the two women talked about the limitations they face as women in the Gulf kingdom. The video garnered over 700K views on YouTube (see video above) and encouraged other women to talk about and engage in driving actions.

- the #Women2Drive positive deviance actions were extended by inviting women to apply for driving licenses and then, when their applications are inevitably rejected, to file lawsuits.

- the campaign drew international support over a number of years, which helped to keep it on the agenda and under the spotlight of global attention, particularly Amnesty International and Freedom House.

In September 2017 it was announced that the ban on women driving would end in June 2018. As the New York Times reported, ‘the ban has long marred the image of Saudi Arabia, even among its closest allies, like the United States, whose officials sometimes chafed at a policy shared only by the jihadists of the Islamic State and the Taliban’.

The success of the campaign has fed into a wider campaign in Saudi Arabia to end the guardianship system #IamMyOwnGuardian #StopEnslavingSaudiWomen, which started in 2016.

- This case study has been adapted from #BeyondTheClick: a toolkit for exploring global digital citizenship by 80:20 Educating and Acting for a Better World

Further reading:

- Saudi Arabia to allow women to obtain driving licences, September 2017, The Guardian

- womensrights.informationactivism.org