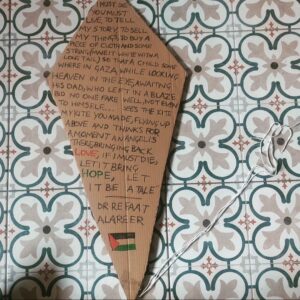

Photo credit: Just a crazy crazy world by Stefano Corso (14.07.06) via Flickr (BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Published on Africa Is A Country, a version of this essay by research fellow at The Makerere Institute of Social Research, Yahya Sseremba, was presented at a teach-in event organized by the 32° East Ugandan Arts Trust on December 7, 2023 in Kampala.

How should we understand the vicious violence that the state of Israel is unleashing indiscriminately on Palestinian children, mothers, fathers, hospitals, schools, and places of worship in Gaza? Most importantly, how does this bloodshed relate to our own history of political violence in Uganda and Africa?

To begin with, both Uganda and Israel are nation-states. This means that each of these states exists in the name of a national community that imagines itself in terms of certain purportedly shared biological, or ancestral, or cultural, or religious characteristics.

Uganda, on the other hand, exists in the name of indigenous communities spelled down in the Third Schedule of the 1995 Constitution. To establish a state in the name of a specific community has often led to much conflict between the national community and political minorities (minority here refers to communities that are not part of the national community regardless of their numerical strength). To minimize these conflicts, nation-states have typically dealt with the political minorities in three ways.

First, by eliminating minorities through mass killing and mass expulsion. This is what the Europeans have done wherever they have settled, from Europe itself to North America and from Australia to New Zealand. Second, by subjecting minorities to systematic discrimination that sometimes escalates into full-scale apartheid, as witnessed in South Africa and now Israel. Third, by tolerating minorities (for example, granting them citizenship rights) without recognizing them as members of the national community.

Israel did not take the route of tolerance. The state of Israel was founded as an exclusive homeland for Jews. To establish such an exclusive homeland for Jews means to get rid of the existing Palestinian population. Indeed, the foundation and expansion of Israel has proceeded with the mass displacement and mass killing of the Palestinians.

It should be clarified that the mere movement of Jews to Palestine is not enough to lead to endless violence between Jews and Palestinians. Rather, this endless violence is rooted in Zionism, an extreme manifestation of the nationalism of the nation-state, which insists that Jews must have an exclusive homeland in Palestine in which non-Jews have no meaningful place. This means that the Palestinians must be eliminated through ethnic cleansing or at least dominated through apartheid.

This is the very ideology that led to the slaughter of Jews in Nazi Europe. The Nazis insisted that Europe belonged to “pure” white peoples, and that the rest had no place there. Nazism and Zionism are rooted in the same logic of the nation-state, which privileges a rigid notion of biology or ancestry or culture as the basis for political association.

The European powers upheld this Nazi logic when they advanced the Zionist aspiration for a separate homeland for Jews. The European powers could have dismantled the logic of Nazism—beyond simply punishing individual Nazis—by exploring ways in which peoples of different races and cultures could coexist in Europe.

Instead, they rewarded the logic of Nazism by supporting the creation of a separate homeland for those who were persecuted in Europe. This never solved the problem of violence; it only reproduced the same in Palestine.

Uganda, meanwhile, has carried out four mass expulsions of non-indigenous communities, including the Kenyan Luos, the Indians and the Banyarwanda.

The logic that leads to the displacement of Palestinians in historic Palestine is the same logic that leads to the expulsion of non-indigenous communities in Uganda. This is the divisive logic of the nation-state of which Zionism is only an extreme, but by no means exceptional, manifestation.

The logic of the identity-based form of political association known as the nation-state pits societies against one another at two levels. First, it pits the national community against minorities, as we have explained. Second, it sometimes divides the national community internally along sub-national lines.

In Uganda, the political community should be conceptualized at two levels. The first level involves the national community, which is an association of indigenous communities as defined in the Constitution. To be considered a full Ugandan citizen with permanent citizenship status, one must prove membership of one of these indigenous communities. Citizens of non-indigenous origin can be stripped of citizenship under certain circumstances. The second level is the regional community, which is composed of the dominant ethnic group of a particular region or district of Uganda. Every indigenous ethnic group of Uganda is assumed to have an ancestral homeland in a particular territory of Uganda. Groups and individuals that live outside of their purported ancestral districts risk forfeiting certain rights like access to land, employment in district-based public offices, district quota university scholarships, and so on. The endless ethnic conflicts in the districts of the Rwenzori, for instance, are based on contestations around which group is indigenous to these districts and which one is not. This kind of sub-national, identity-based contestation is also evident in Israel between the Ashkenazi and Mizrahi Jews.

There is nothing new about discrimination based on perceived biological or cultural or religious differences. But there is something particularly problematic about modern nation-state discrimination. Modern discrimination is entrenched in the structure and logic of the state because the state is an identity-based state.

Pre-modern and modern forms of discrimination

By pre-modern I mean the period before the establishment of the centralized structure of power known as the modern nation-state. This period differs from one part of the world to another. In Africa and the Middle East, the nation-state is a recent colonial creation.

Before the development of centralized power, there were different forms of political powers that coexisted in society. The rulers, whether one calls them kings or emperors or sultans, held one form of political power, which we shall call royal power. In places like Buganda, this royal power could be further subdivided into the power of the kabaka (king), the power of the namasole (queen mother), the power of lubuga (royal sister), and so on.

But there were also other society-based political powers held by the clans, the shrine, the church, and so on. In the lands of Islam, the mufti produced (i.e. interpreted) the Shari’ah (Islamic law), which coexisted with the laws made by the rulers. The mufti’s legal opinion, though nonbinding, informed many judgments in the courts of law. Thus the mufti was an important political authority even if he held no government office. Elsewhere, the church made its own laws that coexisted with the laws of the kings and emperors.

This kind of political arrangement in which power was spread rather concentrated in one entity means that there was no single political authority that determined who should be included in or excluded from the political community. An outsider who was rejected by one clan could be admitted by another. A heretic who was persecuted in one village could find peace in a neighboring village. A cultural stranger who was denounced today could be accepted tomorrow. The terms of inclusion and exclusion were contestable, flexible and abstract. There was no permanent or universal outsider.

The modern state, on the other hand, does two things. First, it centralizes and monopolizes all political power, including the power to determine who is a citizen and who is not. Even if a clan in northern Uganda admits a Somali as its member, the state of Uganda reserves the authority to revoke the citizenship of this new clan member.

Second, the modern state institutionalizes and reifies the criteria for determining who is included and who is excluded in the political community. In Uganda, a full citizen must be a member of an indigenous community that was living within the borders of Uganda by February 1, 1926, as noted earlier.

This makes the nation-state an inherently and extremely discriminatory form of political association with no precedent in history. It seeks to dominate society completely with specific emphasis on marginalizing and colonizing certain sections of society.

To mitigate the marginalization of the minorities, liberals (such as John Locke) introduced the ideas of tolerance within the framework of secularism. The liberal nation-state creates two spheres, namely, the public sphere and the private domain. The private is the domain of religion and other cultural identities while the public is the sphere of reason.

To ensure peaceful coexistence between the national community and the minorities, liberals prescribe that matters to do with religion, culture, and identity should be personal business confined to the private domain. Public principle, including state law, should be based on reason, not religion or any other cultural prejudice. The assumption is that reason is neutral and objective rather than being socially constructed. How can reason and public principle be neutral and objective in an identity-based state? How can an identity-based state produce a law that is detached from the cultural identity of the state?

But there is even a bigger problem. If liberal tolerance appears to have worked, it has only worked where the minorities are too weak to threaten the dominance of the national majority. Where the minorities gain some power and influence, they are seen as a threat that must be dealt with. The rising popularity of far right parties in Europe is partly fuelled by the supposition that the minorities, including the Muslims and migrants, are purportedly gaining ground in these countries.

Indeed, Zionist ethnic cleansing possibly seeks to reduce the Palestinians to small manageable numbers that could eventually be tolerated without threatening the dominance of the Jewish national community. The liberal notion of tolerance only requires the national majority to tolerate the minorities, but it does not ask why there should be a national majority in the first place. Thus liberal tolerance does not offer a meaningful solution to the fundamental problem of the nation-state, which is rooted in the distinction between the national community and the minorities.

All liberal interventions have failed to end ethnic cleansing because liberalism operates within the framework of the nation-state. Liberalism has no critique of the nation-state as nation-state—it only critiques certain manifestations of the nation-state. In other words, liberalism has no critique of the problem itself; it only focuses on certain manifestations of the problem.

It is this conceptual narrowness of liberalism that prompts political actors to create more nation-states as a solution to the violence of the nation-state. When Jews were persecuted in Europe, the European powers could not think of a better solution than creating a separate nation-state for Jews. The consequence was to reproduce the violence of the nation-state, this time in the form of Zionist ethnic cleansing in Palestine. It is for this reason that the ongoing problem in Palestine cannot be meaningfully addressed by resorting to the so-called two-state solution.

If such a solution was to be adopted, what would happen to the non-Jews living in the Jewish state and what would happen to the non-Palestinians living in the Palestinian state? Considering that neither Jews nor the Palestinians are a homogenous category, how would the state deal with internal differences in the form of religious sects and ethnic factions of its national community?

Unfortunately, there is so far no conclusive alternative to the divisive character of the nation-state. But this divisiveness can be mitigated or exacerbated. To this effect, I will discuss two sets of cases, beginning with Tanzania and Uganda. Both Tanzania and Uganda inherited racial and ethnic problems from the colonialists. But the two countries approached these problems differently. Tanzania today is the most stable country in the east African region. Uganda remains unstable.

This is partly because Tanzania and Uganda adopted different conceptualizations of citizenship. The main categorizations of citizenship in Tanzania—citizenship by birth and by descent—define a Tanzanian as any person born in Tanganyika or Zanzibar before the independence of Tanganyika or before or the so-called revolution of Zanzibar. The same applies to the offspring of such a person. This definition has nothing to do with race even if Tanzania has sizable Arab and Asian populations coexisting with the black population.

But the main categorization of citizenship in Uganda defines a citizen as a member of an indigenous ethnic group that was living in Uganda by 1926. Ugandan law attaches the main category of citizenship to ethnicity and indigeneity. One cannot get a national ID or passport without proving their membership to an indigenous ethnic group. When a Ugandan goes to the police or applies for university admission, one of the first questions she is confronted with is: what is your “tribe”?

The Ugandan state looks at Ugandan society as nothing but a collection of “tribes.” Why wouldn’t ethnicity become so contentious when it is the basis for political inclusion in the Ugandan political community? By separating citizenship from race, ethnicity, and indigeneity, Tanzania did not need to expel its Arab and Asian populations. But Uganda expelled the Kenyans, the Indians and the Banyarwanda, and it may repeat the same in the future, because it racialized and ethnicized citizenship.

Tanzania challenged aspects of the logic of the postcolonial nation-state because of two possible reasons. The first is the influence of socialism on Julius Nyerere’s political thought. Nyerere conceptualized society in terms of class, not race. Second, the so-called Zanzibar revolution, through ethnic cleansing, had weakened the Arabs and reduced them to a small manageable minority. Thus the Tanzanian majority black population could tolerate and coexist with them peacefully without the fear of being dominated by them.

In Uganda, on the other hand, the Indians dominated the economy and politics. In the logic of the nation-state, such a powerful minority cannot be tolerated. It is not surprising that Ugandan nationalists in the 1960s and the reformers in the 1990s defined citizenship in such a nativist manner that left out the Indians and other minorities. In Uganda, the Indian remains a feared minority whose second expulsion “will be more terrifying than the first,” as Yusuf Serunkuma has warned.

South Africa and South Sudan

In South Africa, white supremacists subjected the indigenous population to a ruthless regime of apartheid. In Sudan, the people of the south fought against marginalization for decades.

In Sudan, the warring parties, especially after the death of John Garang who preferred a solution within the framework of one united Sudan, chose the two state solution because they defined the problem in racialist and culturalist terms. Instead of addressing the fundamental problem of the postcolonial nation-state that makes race, ethnicity and religion as the basis for political inclusion, they decided to create a new postcolonial nation-state along these identity lines. There has never been peace in either Sudan or South Sudan.

In South Africa, on the other hand, the oppressed indigenous population and the white supremacists agreed to end apartheid and coexist as one political community. Compared to Sudan and South Sudan, South Africa is relatively peaceful. But the peace in South Africa is founded on shaky grounds. The deal that ended white rule allowed the whites to retain the economic privileges they had accumulated by dispossessing the indigenous population. With a small minority enjoying privilege at the expense of a dispossessed, impoverished, and disgruntled majority, for how long can the peace hold?

If the Sudan-type two-state solution is conflict-ridden, what lessons can Palestine and Israel learn from the South African one-state solution?

What would it mean for the Palestinians and Jews to live together in the same political community? What compromises need to be made by both sides? To follow the South Africa precedent to the letter would mean that Jews should retain the land and other privileges that they have grabbed from the Palestinians in exchange for Palestinian inclusion as equal members of the political community. But what kind of equality would that be? And what kind of peace would it yield?

From an empirical perspective, the South African example offers only partial hope. But empirical realities alone, contingent and transitory as they tend to be, cannot unilaterally dictate the framework of our thinking.

Political theorist Mahmood Mamdani is thus right to take South Africa as an important experiment and site of abstraction as we explore ways in which different races and cultures can coexist without reproducing the polarizing narrowness of the nation-state.

- Yahya Sseremba is a research fellow at The Makerere Institute of Social Research. Dr. Sseremba’s latest book is America and the Production of Islamic Truth in Uganda.

- This article was originally published on Africa is a Country in December 2023 and was shared under creative commons license CC BY 4.0 Deed Attribution 4.0 International. See the original article here.