In one of his less well-known war poems Wilfred Owen looks forward to a future when men and women no longer do battle for flags but rather strive to improve the human condition. Writing about life in the trenches he provides this thought:

We laughed, -knowing that better men would come,

And greater wars: when each proud fighter brags

He wars on Death, for lives; not men, for flags– The Next War, Wilfred Owen’s Collected Poems.

Recent events in Belfast indicate that the future envisaged by Wilfred Owen almost a century ago remains elusive. Men (and it is primarily men) still fight for flags. Ever since the Belfast city council voted to alter its flag policy at Belfast City Hall on December 3rd there have been numerous loyalist demonstrations with a few of them resulting in serious rioting. The city council voted to fly the Union flag only on certain designated days rather than on a daily basis. Since the vote was passed 127 police officers have been injured and 174 people have been arrested.

Flags in Northern Ireland (and elsewhere) have long been a matter of contention, disagreement and occasionally of violence. We often speak of allegiance to a flag and this is especially poignant in a society divided into two blocs each wanting to pledge their allegiance to two different flags. The use of flags in Northern Ireland has been a divisive issue ever since the formation of the state. The Special Powers Act of 1922 was used by the Unionist government to impose restrictions on the flying of the Irish tricolour while in 1954 a specific law, the Flags and Emblems (Display) Act, was enacted by the Northern Irish parliament. Under this Act the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) had a duty to remove any flag from public or private property which was likely to cause a breach of the peace, but legally exempted the Union Flag from ever being considered a breach of the peace. In effect this meant that the Irish tricolour was the flag which was removed most often by the RUC.

Given this history, it is no surprise that flags remain one of the most divisive issues in Northern Ireland. It is equally clear that the Belfast city council’s decision to change its flag policy was destined to, at best, irritate the unionist community and, at worst, foment disorder. This is not to say that the disorder and violence is, in any way, excusable but simply that it could have been foreseen. One must ask whether the Sinn Fein, SDLP and Alliance members of the Belfast city council were wise in carrying through this vote. In any normal society such a decision might go unnoticed. I certainly never notice whether flags are flying on public buildings in Malta. However, Northern Ireland is not yet a normal society. The peace process, as the term implies, is a work-in-progress. This needs to be acknowledged by decision-makers who need to weigh very carefully the likely impact of their decisions.

The other aspect of this matter refers to the willingness of a portion of the population to resort to violence in order to advance their political aspirations. The violence by loyalist protesters during some of the demonstrations is one reminder that political violence has not disappeared altogether from Northern Ireland. The continuing threat posed by dissident republican groups, highlighted recently by the Chief Constable of the Police Service of Northern Ireland, is another indicator of this.

As the danger of violence remains there are two aspects that continue to require attention: one is a commitment to work with communities on issues of human rights, citizenship and democracy. The move away from violence requires this long term commitment. The other aspect is an effort to build confidence between and within communities. This will create the time and space required for the long term work to flourish. Politicians should scrutinise their words and actions to ensure that they do not render the long term work even more fraught with difficulties than it inherently is. Wilfred Owen’s aspiration that men do not fight for flags requires not that flags be taken down from their flag poles but that flags lose a little of their meaning.

Further reading | BBC News, Union flag protests: Twenty-nine officers hurt in Belfast, 12th January 2013.

_______________________________

Brief guide to flags in Northern Ireland

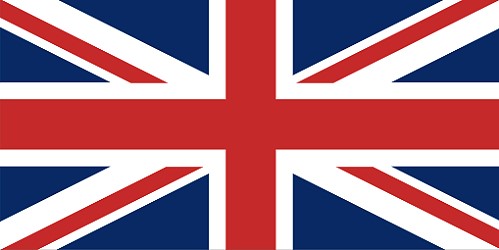

The Union Jack – the official flag of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

It is composed of the three crosses superimposed on each other: the cross of St. George (England), St. Andrew (Scotland) and St. Patrick (Ireland). The unionist and loyalist communities of Northern Ireland are deeply attached to the Union Jack. Conversely, the nationalist and republican communities of Northern Ireland are averse to it as a symbol of British repression.

The Irish tricolour is the flag of the Republic of Ireland and is considered by the nationalist and republican communities as the flag of the whole island of Ireland. The unionist and loyalist communities consider it as the flag of a foreign (and sometimes enemy) country.

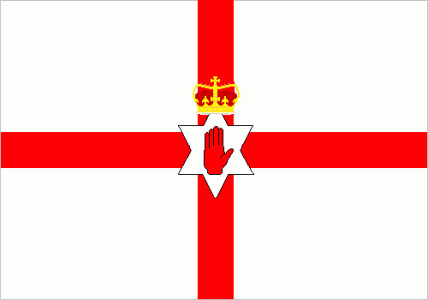

The Ulster Banner, the flag of the government of Northern Ireland between 1953 and 1972. Once the Northern Ireland government and parliament were dissolved in 1972 the flag ceased to have any official status. It is still used by some unionist and loyalist communities and also by some Northern Ireland sports teams.