For human rights activists, the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a sacred document. Its 30 different articles outline the political, economic, social rights that we are all entitled to – no matter who we are – because we are born human. By such reckoning, the universality of human rights is beyond question.

Created in the aftermath of the Second World War and the horrors of the holocaust, the declaration was an attempt to ensure that such a catastrophe could never ever take place again. The humanity of all peoples was to be acknowledged beyond recognition by all states, with no exceptions. From this point on, all humans were to be regarded as free and equal,

“with no distinction given to their race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.” – Article 2, UDHRs

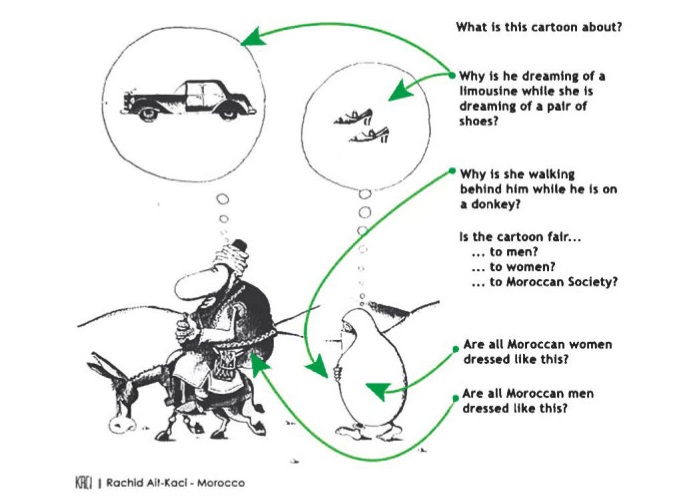

In spite of this, the universality of the document has been criticised by some, not least by members of the American Anthropological Association (AAA). They argue that by claiming human rights are universal, we ignore and undermine the cultural differences that exist between societies in different parts of the world.

How can one single document claim to represent every single person in the world, when our experiences are so different?

Our view of the world and our role in it is shaped by the society in which we live; and therefore our moral standards, the values which we emphasise as individuals, depend on our cultural upbringing. As a result, how can the UDHR possible have the same meaning for everyone in the world?

For critics, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a Western-biased document which fails to account for the cultural norms and values which exist in the rest of the world. More than that, it is an attempt to impose Western values on everybody else.

“The West now masks its own will to power in the impartial, universalizing language of human rights and seeks to impose its own narrow agenda on a plethora of world cultures that do not actually share the West’s conception of individuality, selfhood, agency, or freedom” – Michael Ignatieff

In some ways they are right. Anyone reading the document will note the emphasis on individual rights as opposed to communal rights which tend to be more heavily emphasised in the non-Western world.

But are their arguments misguided? After all, the declaration was written by representatives from all over the world including Chile, China, Egypt, India, Pakistan and Lebanon, none of which would be classified as “Western”. Plus, two-thirds of the endorsing votes came from non-Western countries (48 in favour, none against and 8 abstentions). In addition,

“the members of the drafting committee saw their task not as a simple ratification of Western convictions but as an attempt to delimit a range of moral universals from within their very different religious, political, ethnic, and philosophical backgrounds” – Michael Ignatieff

By emphasising the rights of individuals, the declaration was meant as an attempt to transcend cultural bias in such a way that it became relevant to all, no matter what their upbringing. Nevertheless, some still argue that the declaration represents a neo-colonialist attempt by the West to control the lives of those in the developing world. Such arguments have been used by authoritarian leaders and states to violate human rights (particularly those of women and children) under the guise of enforcing tradition.

For example, Saudi Arabia abstained from the vote on the declaration, arguing that Articles 16 and 18 (the rights for men and women to marry who they choose, and the right to freedom of religion) were in opposition to Islamic faith and teachings which emphasise patriarchal authority.

The UDHR is certainly not perfect, and yes, it can be argued that the document emphasises individualism over community rights. But does this really mean that human rights are not universal? In their eagerness to promote the importance of cultural diversity and group rights, critics forget that all cultures are composed of individuals and regardless of our cultural upbringing; no two people think exactly the same.

Group rights are great in theory, but they can be used to suppress individuals who do not fit the hegemony of that group. By protecting individuals, human rights do not diminish the group, but merely ensure the protection of each and every individual within it. And in addition, culture is not static, but constantly evolving as people come into contact with new ideas and concepts. Because some cultures do not emphasis certain rights at the moment, does not mean that will always be the case.

In any case, human rights are compatible with cultural diversity. Every culture can pursue its own vision of a good life, as long as it doesn’t impinge on the rights of the individuals who exist within that culture. As Ignatieff again states,

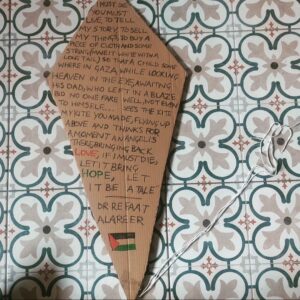

“This individualism renders human rights attractive to non-Western peoples and explains why the fight for those rights has become a global movement.

The language of human rights is the only universally available moral vernacular that validates the claims of women and children against the oppression they experience in patriarchal and tribal societies; it is the only vernacular that enables dependent persons to perceive themselves a and as moral agents and to act against practices- arranged marriages, purdah, civic disenfranchisement, genital mutilation, domestic slavery, and so on-that are ratified by the weight and authority of their cultures. These agents seek out human rights protection precisely because it legitimizes their protests against oppression.”

Even countries where one might expect a cultural clash between the “Western” rights outlined in the UDHR and local traditions are not as common as one might expect. Three quarters of all world states have endorsed the declaration with a ratification rate of 88% and it has also been argued that a progressive interpretation of Sharia law can be compatible with universal human rights.

The declaration might not be perfect, and certainly there are issues regarding the enforcement of such rights. But to diminish them on the claim that they are “Western” and therefore incompatible with other cultures is dangerous. What matters is the purpose of human rights – not their origins – and their ability to protect the individual interests of the powerless, in all cultures.

Further reading

- Ignatieff, M. 2001. The attack on human rights. Foreign Affairs, pp. 102—116 (available online).

- For an animated history that reads like a political thriller on the drafting of the declaration and the politics of consensus in a bipolar world following the wreckage of WW2, see Mary Ann Glendon’s book A World Made New: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (2002).

- See our introductory guide to human rights for community and youth educators.

- See our introductory guide to women & development.

Urgently needed and timely new resource from Afri

Ciara Regan reviews Afri’s latest resource, Sowing Seeds of Peace, for post primary teachers which is adaptable and immediately useful across a range of school subjects.

It’s international women’s day. Don’t forget to tag us now that you feel #prettypowerful

From getting out to vote and entertaining two children off school due to it being a make-shift polling station, Ciara Regan reflects on international women’s day 2024.

Punching above its weight

Juan Acevedo-Ossa explores South Africa’s case against Israel as the latest example of its ability to act as a normative superpower, exceeding the great powers in shaping global moral discourse.

Empathy in a Divided World – workshop

Join us for this online session Empathy in a Divided World led by Brighid Golden to discuss how educators can respond to the challenges of selective empathy, both for ourselves personally and with others in our different settings.

What does Palestine have to do with Africa?

How does Israel’s current aggression on Gaza relate to Africa’s own history of political violence in Uganda and Africa?

‘What life is this?’: Escaping Ukraine’s occupied territories

From food shortages to informants, eight evacuees talk about life in Russian-occupied towns