With his encyclical Laudato Si: On Care for Our Common Home (available online as a long-form letter) Pope Francis has entered the fray not just on the environment and its future but also more broadly on the ethics and impact of dominant models of economic development and ‘extreme’ consumption. His encyclical highlights the fact that our fossil-fuel based, ‘throwaway culture’ coupled with our ‘irrational confidence in progress and human abilities’ and a ‘blind confidence in technical solutions, is ‘actually making our earth less rich and beautiful, even more limited and grey’.

In keeping with the vast bulk of scientific research and evidence,  Francis argues that climate change is not just a ‘global problem with serious implications’ for people and planet, but is also based on substantial and growing international inequality whose impact is felt disproportionately by the world’s poorest people. It is also rooted in a perverse logic that insists on short-term gain for some at the cost of long-term loss for all.

Francis argues that climate change is not just a ‘global problem with serious implications’ for people and planet, but is also based on substantial and growing international inequality whose impact is felt disproportionately by the world’s poorest people. It is also rooted in a perverse logic that insists on short-term gain for some at the cost of long-term loss for all.

Contrary to much of western popular perception and (ill-informed) debate, he highlights the reality that the resources and wealth of poorer countries continue to fuel the development of richer countries at huge present and future cost. He calls on the rich of the world to recognise the impact of their wealth and way of life and begin paying their ‘grave social debt’ to the poor by taking concrete steps on climate change and sustainable ways of living.

‘The developed countries ought to help pay this debt by significantly limiting their consumption of non-renewable energy and by assisting poorer countries to support policies and programmes of sustainable development.’

Continuing denial of the issue, obstructionist attitudes, indifference to its realities and impacts (even locally), a fatalism that argues little or nothing can be done leading to a ‘numbing of conscience’ constitutes, according to Francis an undeniable risk to humanity. In this he echoes much that the vast majority of environmental scientists have agreed (97% according to the latest research).

The 180-page encyclical is not simply a moral call for action on, for example, phasing out our blind belief in and use of fossil fuels, but is also a sustained critique of modern ‘development’ flavoured with a sharp anger at the indifference and ‘green rhetoric’ of the powerful; a concern for the poor (as outlined in so many previous papal encyclicals) and a call for public engagement and activism.

The encyclical insists that

‘those who possess more resources and economic or political power seem mostly to be concerned with masking the problems or concealing their symptoms’.

This promotes a failure to respond morally or practically and points to the loss of shared responsibility for either our fellow men or women – a principle upon which all civil society is founded’ (this is particularly evident in the present ‘debate’ on migration where the language and sentiments have become increasingly shrill and threatening). The many ‘special interests’ (including ‘economic interests’ especially those of ‘finance and consumerism’) routinely trump the common good, manipulating information and opportunities in their own interests and agendas.

The potential relevance of the encyclical for the climate change is considerable not least in the analysis of the causes of the environmental crisis and its many strands and dimensions – unquestioned growth for its own sake; privatisation of public goods and resources; environmental degradation and pollution accompanied by a refusal to recognise the current and future costs of dominant economic models.

In particular there are a number of overarching arguments offered in the encyclical that have immediate and direct relevance across the Developed World in particular.

- The growing disrepute in which politics is held by an increasing number of people on account of corruption and the failure to act for the common good and for a lack of leadership on issues such as environment and climate change

- A weak awareness across many strands of society of the need to protect and nourish the global environment and resources for this and future generations

- The need to discuss and debate lifestyles, individual and social responsibilities in this regard and the impact of those responsibilities in the wider world, especially for the poor and the planet

- The urgent need to realistically promote and resource education for ecological citizenship and not simply in schools (for this is not a ‘schools agenda’ through which society can wash its hands)

- The need for all of us to carefully consider the needs of young people as regards the consequences of the environmental crisis in the decades ahead.

Perhaps the central challenge offered by Francis is the need for all to accept the principle of shared responsibility and to challenge the growing dominance of individualism, individual choice, individual ‘rights’ without consideration of their consequences. In concluding the encyclical, the Pope suggests:

‘We have to dare to speak of the integrity of human life, of the need to promote and unify all the great values. Once we lose our humility, and become enthralled with the possibility of limitless mastery over everything, we inevitably end up harming society and the environment.’

This encyclical is not just for believers – it speaks to each and every one of us.

…………………………………………………………………….

For more…

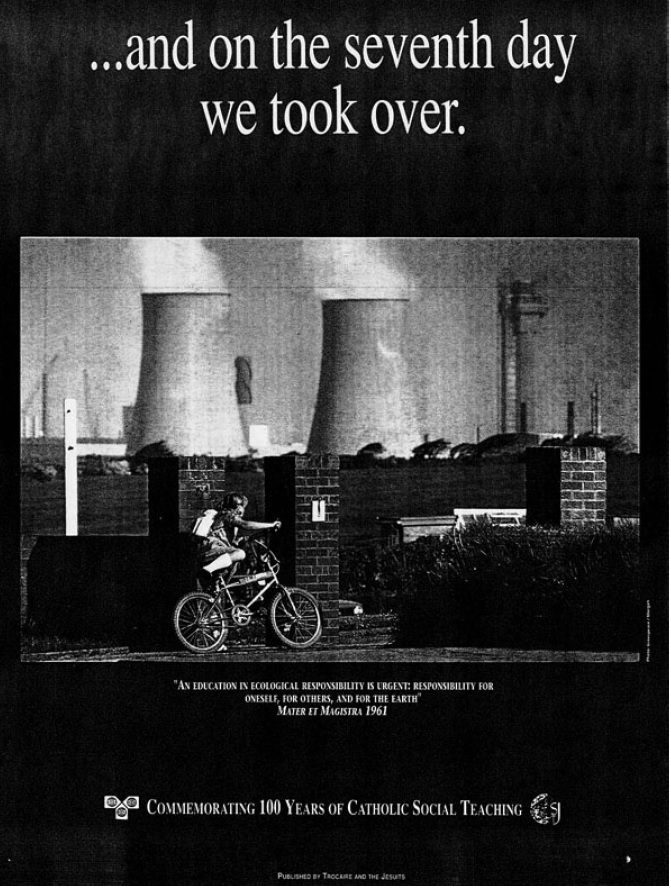

Download the posters and use the activities from In Words and Deeds: 100 Years of Catholic Social Teaching – a poster pack (1991) produced by Trócaire (1991), The Irish Jesuits The National Conference of Priests in Ireland and the Catechetical Association of Ireland.

Watch a three-minute introductory guide to Catholic Social Teaching (2014) in 3 minutes:

Watch The Cry of the Earth: a call to action for climate justice (2014) relaunched by the Irish Bishop’s Conference (interview with Lorna Gold, head of policy and advocacy with Trócaire, on climate change, climate justice and catholic social action):

Visit Social Action Office for an excellent overview of Catholic Social Teaching and a summary of its key concepts.