‘Meanwhile in other parts of the world, events continue…’; cue solemn-faced rugby player reminding us that while the World Cup goes on millions remain hungry and requesting viewers to contribute £5.00 to tackle the issue. We have become used to sports and sports celebrities highlighting and taking on ‘good causes’ as part of the broader celebrity-based advocacy of such issues.

I am not one to automatically decry or ridicule such involvement – it can play an important role in highlighting issues and in keeping them in the public view and it can even embarrass politicians and technocrats into taking action (especially when publicity photo-ops are available!). Nor do I automatically question the bona fides, honesty or authenticity of many celebrities as they promote ‘their’ cause; part of my work is to encourage just such interest and identification.

However, in the case of the Rugby World Cup and  its espousal of the issue of world hunger, I found myself intensely angry and agitated – not at the players who highlighted the issue or even at the International Rugby Board or the tournament organisers. What made me angry was that a most fundamental human right – that to food and life – has become once again, after so many decades and so many tens of thousands of words and promises (by world ‘leaders’ from across the globe), a matter of voluntary individual action in the form of cash contributions.

its espousal of the issue of world hunger, I found myself intensely angry and agitated – not at the players who highlighted the issue or even at the International Rugby Board or the tournament organisers. What made me angry was that a most fundamental human right – that to food and life – has become once again, after so many decades and so many tens of thousands of words and promises (by world ‘leaders’ from across the globe), a matter of voluntary individual action in the form of cash contributions.

It is nothing short of outrageous and immoral that an issue – world hunger – that could and should have been eliminated decades ago at so little cost continues to blight the lives of some 800 million plus human beings at a time when the world has never been richer or better informed.

Its continued existence amidst the squandering of immense quantities of resources (on, for example, militaries worldwide – amounting to over $1.7 trillion in 2014 as against $30 billion per year to eradicate hunger) could readily be classed as ‘evil’.

Hunger in the world is not an ‘accident’, an unforeseen result of acts of nature over which we have little control; thanks to the work of the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food and that of many non-governmental organisations we know who the hungry are (e.g. those trying to live on less than 1.5 hectares for their livelihood, seasonal agricultural labourers working on large plantations, the urban poor and many indigenous people) and in ‘normal circumstances’ when they are likely to be hungry.

We also know the primary causes of their hunger (low agricultural productivity, poverty, conflict, poor governance, unjust trade and climate change) and what interventions are best likely to resolve the issues.

The annual State of Food Insecurity in the World report published by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN and the many reports of the Special Rapporteur provide a detailed analysis and agenda for action including an assessment of cost. Reducing action on hunger to voluntary individual goodwill or to the interventions of sports personalities or celebrities is a direct insult to the poor and hungry as well as a searing indictment of world ‘leaders’ over many recent decades.

How many times have we heard the refrain – ‘never again will a child go to bed hungry’?

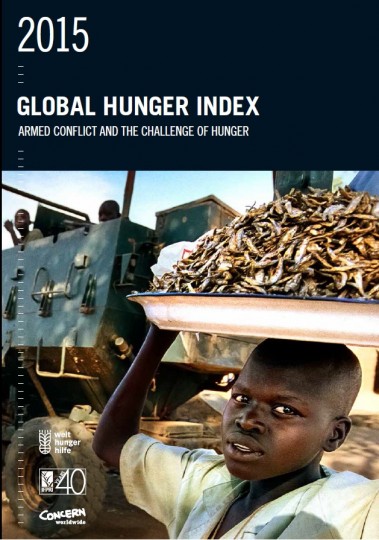

Despite progress in reducing hunger worldwide (it has fallen by 27% since 2000), hunger levels in 52 of 117 countries analysed in the 2015 Global Hunger Index Report remain  ‘serious’ (in 44 countries) or ‘alarming’ (in 8 countries) with the highest levels recorded in the Central African Republic, Chad, and Zambia. Global hunger remains a key challenge with 1 in every 9 people worldwide ‘chronically undernourished’ with more than 25% of children too short for their age due to nutritional deficiencies. Nearly half of all child deaths under the age of five are due to malnutrition, which claims the lives of about 3.1 million children per year. As the current UN Special Rapporteur put it:

‘serious’ (in 44 countries) or ‘alarming’ (in 8 countries) with the highest levels recorded in the Central African Republic, Chad, and Zambia. Global hunger remains a key challenge with 1 in every 9 people worldwide ‘chronically undernourished’ with more than 25% of children too short for their age due to nutritional deficiencies. Nearly half of all child deaths under the age of five are due to malnutrition, which claims the lives of about 3.1 million children per year. As the current UN Special Rapporteur put it:

‘The right to food is not about charity, but about ensuring that all people have the capacity to feed themselves in dignity’.

They should have the effective right, opportunity and resources to feed themselves and not be dependent on the charity or generosity of others.

Food is now increasingly recognised as a human right – something that governments should be made accountable for and something which national and international institutions must be challenged on. Just as genocide, torture and crimes against humanity are recognised as gross violations of human rights requiring ‘official’ action at a variety of levels, so too the right to food.

To date, only 22 countries have enshrined this right to food in their constitutions either for all citizens or for children specifically. However, the shocking reality is that no country has yet introduced and implemented legislation to implement the right and it is specifically here that those who want to eradicate hunger should focus their energy and time.

Individual donations of cash no matter how effectively used will never eradicate hunger as they fail to address its systemic causes – unjust trade, poverty, land tenure, discrimination against women etc. The Rugby World Cup is to be congratulated for highlighting the issue but the response it offers falls well below what is required; it needs to highlight the systemic and political nature of the issue and encourage its viewers to do likewise.