Deirdre Walsh reports on making the journey to Calais as part of the Ireland Calais Refugee Solidarity convoy in October 2015.

During the summer of 2015 I finished up my MA in Development Studies in the Kimmage Development Studies Centre in Dublin. My research explored how intercultural learning through art and creative methodologies can be transformative for participants and support the building of intercultural communities, particularly in the light of growing global migration and increasing diversity.

Transformative learning theories, issues related to intercultural dialogue, and grassroots community-based actions were in my mind, as like everyone else, I watched and listened in sadness and in anger at the unfolding ‘refugee crisis’.

This crisis has been happening for many years, but as we know it hasn’t been a focus of the media, and therefore hadn’t come to the awareness of many people in Ireland and Europe until this late year. Why is this?

Simply, the number of people trying to gain access to Europe in search of a better life has increased dramatically.

Global inequality has come knocking on Europe’s door, with ever louder knocks:

Responding in solidarity through shared values and actions

‘Cork Calais Refugee Solidarity’ was initiated during the summer of 2015 by a small group of people who wanted to do something, and it quickly snowballed into a massive volunteer-led grassroots network of people around the country leading to the creation of ‘Ireland Calais Refugee Solidarity’, mobilised largely through Facebook.

I went along to a volunteer meeting in August in Dublin city centre, the night before the heart-wrenching photo of the little boy Alan Kurdi who died tragically crossing the Mediterranean Sea was shared in the media. That photograph acted as a loud wake-up call to the unnecessary deaths of innocent people trying to flee persecution, and created a turning point of sorts in terms of the mobilisation of people in Ireland who wanted to do something.

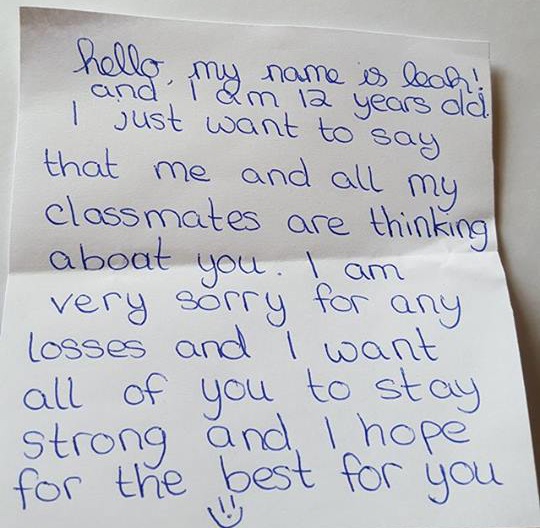

The Ireland Calais Refugee Solidarity group filled that space, giving people an opportunity to give physical donations of items needed in the camp in Calais, and to volunteer their time by setting up collection centres and sorting and packing donations ready for convoy. It also gave people an opportunity to meet with others and to form a network of solidarity in Ireland between people of diverse age groups, cultures, religions, languages and nationalities.

It has been an inclusive movement of people all with the one goal; to work in solidarity with people who are refugees around the world.

The word ‘solidarity’ is key as it embodies both ‘values’ and ‘actions’. This is not about charity, it is about working with refugees and organisations that work with refugees that know the situation on the ground in places like Calais. It is about acknowledging the strength and resilience of people who have made long arduous journeys and who want what we all want – to provide for and protect their families and to lead their lives as best they can.

The Anti-Racism Network Ireland gives an interesting insight into the difference between charity and solidarity:

“Our overarching aim is to amplify and echo the courage, self-organisation and resilience of people on the move, and in tandem, generate effective forms of solidarity. Solidarity can include organising to respond to people’s basic and humanitarian needs, but ultimately it is a political struggle- one that challenges a border regime that is built on exclusion, other-ing and racism.”

Day 1: on the camp

I was part of a convoy of 54 volunteers and three articulated trucks of donations and building materials that travelled to Calais from the 1st to the 8th of October.

During my first day on the camp I assisted with a litter-collection. An amazing man called Dane from the UK, who comes to Calais regularly with his truck to do a litter-sweep, showed us the ropes.

For the 6000 plus people living on the camp there are few facilities. There are approximately 20 toilets that are permanently blocked, showers for no more than 600 people a day, one hot meal a day for about a third of the camp’s residents, and a few taps in muddy flooded areas for drinking water. Litter is a chronic problem, with nowhere to dispose of it and no collections, people resort to burning litter mountains and inhaling the toxic fumes, leading to the prevalence of respiratory issues with many residents.

In walking around the camp that first day, the first thing I noticed was how friendly and welcoming people were. I expected this to a certain extent, but not the enthusiasm to

engage with us that we experienced. This whole process has been a learning curve for me, and I have constantly been forced to challenge my own assumptions and perceptions.

I presumed that people staying in the camp would be depressed, low and angry. I did come across this, and every individual is different, with a different story and experience, but what struck me most that first day was the strength and hope within people that I met. People I chatted with came from Eritrea, Sudan, Pakistan, Syrian, Afghanistan, Iraq and Palestine.

The camp has been in existence in different forms since 2003, being knocked down and rebuilt on a number of occasions, and the flow of people in to the camp has increased.

The majority of people there are men, over 90%, but the women and children that are there are extremely vulnerable. There is a separate building that women and children can stay in provided by the French authorities, but places are limited and we met many women living on the camp, which is why a building team within our group built a women’s and children’s shelter.

Litter duty and walking with Ahmed

The people I met on the camp are often on my mind, and one of these is Ahmed from Syria. We worked together for a few hours collecting litter in the Syrian area of the camp. The camp tends to naturally divide into different communities, each building shelters to sleep in, a school and shops etc., out of whatever materials they can find.

Ahmed asked me what I thought about people like him before I came to the camp. I said that I knew people would be friendly and I was looking forward to meeting people.

He said that he thinks the media creates a negative impression of people like him.

He asked me to tell people that they are not criminals, before shaking my hand and disappearing in the dusk light into his tent.

A man from Sudan called KD, a young doctor, also worked with us that day, and we recently heard that he had made it to the UK and had met his niece for the first time. Many people we talked to had good reasons for wanting to go to the UK: they had fluent English; they had family there; or they had been there already and had been refused re-entry, for example.

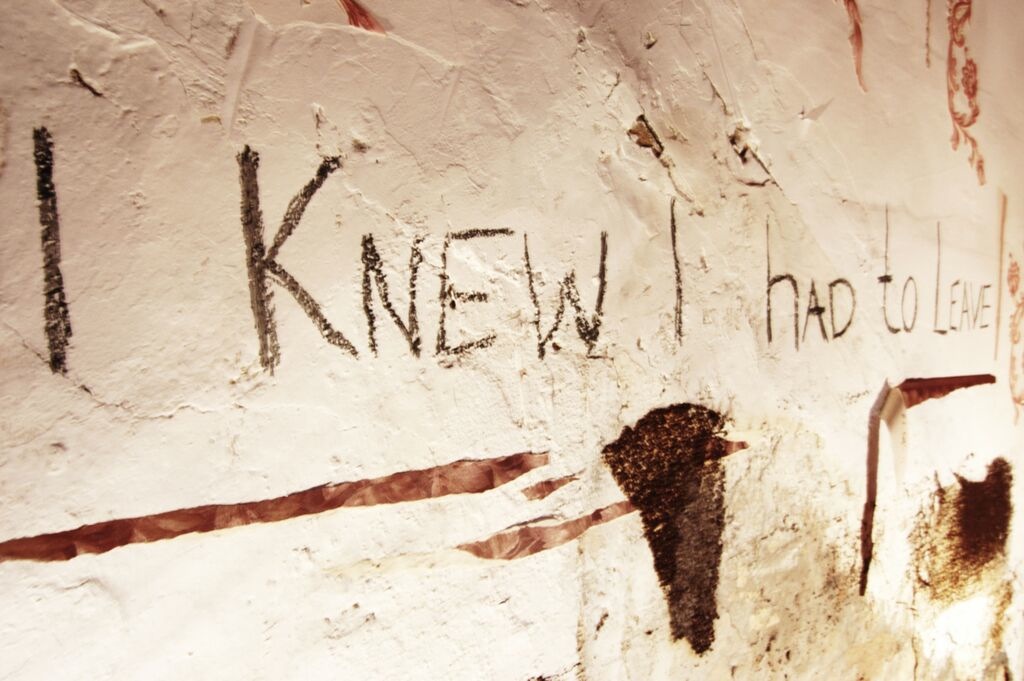

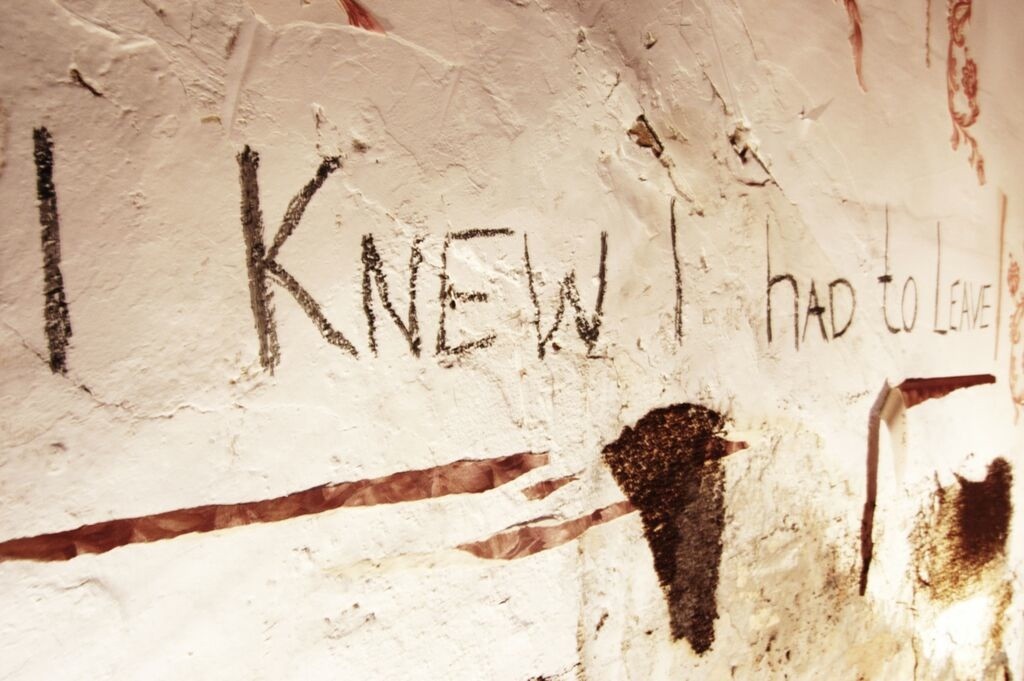

Others had a more utopian view of what life would be like in the UK, and for some Calais was just the end of a long road.

The coat room

I assisted with a distribution of coats during one of my days on the camp, which was organised by L’Auberge the Migrants, a volunteer-led organisation that works with refugees in Calais.

An experienced volunteer named Clare was organising the distribution and she explained that due to the lack of access to resources and the incoming bad weather they could get out of hand very quickly. Our aim was to do this in as dignified a way as possible.

Clare guided us through some important things to keep in mind.

First, to give the men a choice of what coat they wanted as they have little choices they can make in their lives.

Second, to make it as enjoyable and easy an experience as possible.

Third, to relax and watch our body language, as any anxiety in us would spread through the crowd.

So I stood there for hours assisting with the distribution, watching hundreds of men queue in a snaking line that seemed to go on forever. I chatted to those who wanted to chat, and watched the hundreds of faces filing past, some looked so young they couldn’t have been more than 15 years old, and some were elderly and tired.

It was apparently a ‘successful’ distribution because it was calm and organised, but it was one of the saddest things I witnessed that week. It was not fair or just and should not be something that needed to happen.

The Jungle, the tunnels or the motorways

Many brave men and women made dangerous nightly treks to the tunnel, hopping fences and trying to board trucks and trains. Tragically many die by getting knocked down on the motorways, or getting crushed or electrocuted.

The UK recently spent £21 million on security and fences working with the French authorities to keep these people out of the UK. This final hurdle has ultimately proven too high for many to leap.

Watching the groups of people trekking silently back to the camp in the early misty mornings in Calais was one of the most depressing sights I saw. This is in stark contrast with moments of vibrancy I enjoyed on the camp, eating delicious food in the Afghani restaurants, popping my head in to schools to see language classes taking place, and hearing about cultural and music parties in the large dome structure.

Since that visit in October other teams and individuals have gone back to Calais from the Ireland Refugee Solidarity group, with some moving there indefinitely, including a friend who has worked with others to set up a much needed youth centre on the camp for the many unaccompanied minors living there.

Others have gone to Lesvos in Greece.

The warehouses full of donations in Ireland have been finally emptied on trucks that went to Calais, Hungary and Greece. The practical solidarity with Calais and other areas in Europe continues through volunteering, creative projects and advocacy work.

This is where the real challenge lies: how do we stand in solidarity with refugee and migrants and ensure that those in decision-making positions in Ireland and Europe take action that focuses on people and not borders?