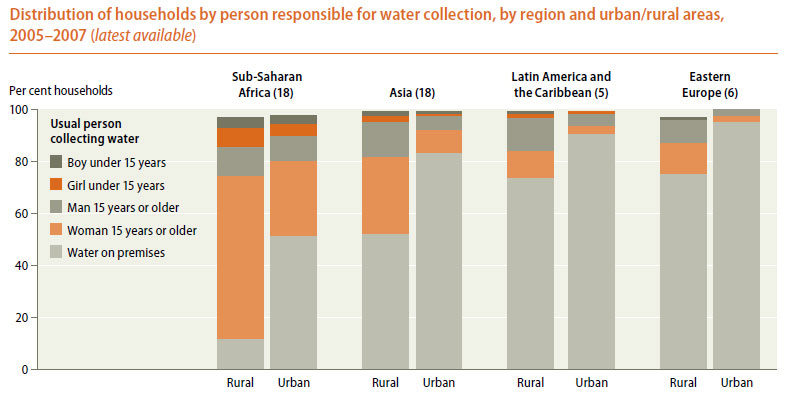

As ever, there’s good news and bad news. The good news is that the MDG Goal to increase the population with access to safe drinking water was met in 2012. But, the bad news is that the focus on ‘safe’ water hides a major issue. People (here read predominantly women) are spending ‘crazy amounts of time collecting this water’ argues environmental health specialist Jay Graham. Because of widespread gender inequality, females are saddled with most of the unpaid chores and water carrying is just one of them.

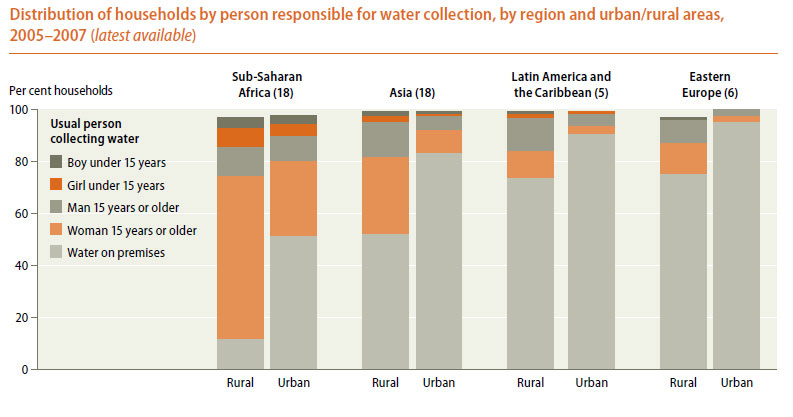

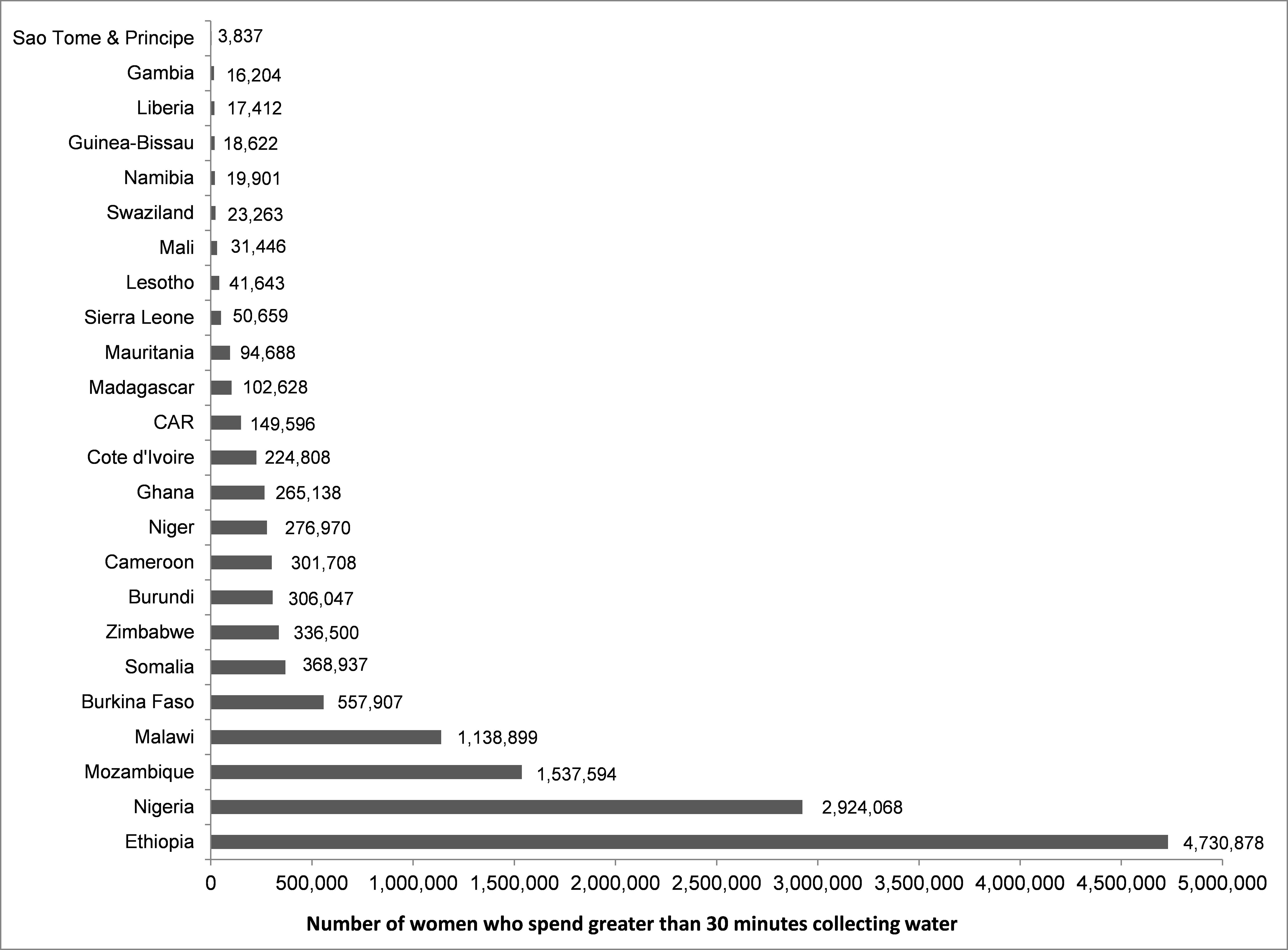

Although essential, it’s a physically demanding, time-consuming responsibility and one that almost always falls to females, according to Graham who, along with colleagues from the Milken Institute School of Public Health at the George Washington University have published a new study analysing the data on water collection from 24 sub-Saharan African countries. They found that in all the countries studies, in households where a family member had to spend more than 30 minutes to collect water, the primary collectors were women. The figures ranged from 46% in Liberia to 90% in Cote d’Ivoire and the gender gap remains when the job is seen as children’s work; 62% for girls versus 38% for boys.

Note: various figures are available for the time women spend in collecting water worldwide; a 2012 UN MDG survey of 177 countries revealed that the figure is an estimated 40 billion hours.

The research highlights that in these 24 countries, there are an estimated 13.5 million women (and 3.4 million children) who are responsible for water collection trips that take 30 minutes or longer. To collect the water, a woman usually carries a jerry can, a plastic container, originally filled with cooking oil that has been cleaned and when full holds 5 gallons and weighs about 40 pounds. In many places in sub-Saharan Africa, the woman is most likely simply carrying the can rather than using a wheelbarrow or a barrel that could be rolled home. We are all (too) familiar with this ‘African image’.

Collecting the water is often not straightforward – the terrain is routinely uneven with many obstacles on route; the path to the water source may change frequently; before setting off, a woman must figure out which pump or well she can visit to actually acquire water on any given day. And, women may make this trip multiple times on the same day. There are seasonal shortages and rations that may complicate this decision and lengthen the trip.

Once a woman gets to a water source, she can expect to spend even more time waiting in line. When there’s just a single hand pump, progress is slow. It’s common to leave a jerry can to hold your spot, notes Graham, who has seen rows of them stretching out for many feet. If the woman lives close enough, she may return home to do domestic chores. If not, she may just hang out and wait her turn.

And then, the hardest part – carrying the water home. The study reveals just how hard this work is and highlights the additional reality that very many of the women and girls who regularly carry water are living in poverty and experience undernutrition frequently. Long walks with such a heavy load take their toll health-wise, according to Jo-Anne Geere, a lecturer at the Norwich Medical School at the University of East Anglia who has researched the issue in her work on South Africa. She found that carrying such heavy loads on one’s head is associated with a particular pain pattern, with discomfort in the upper back and hands and an increased risk of headaches (she thinks due to disc compression in the neck). In one survey she collected data from six villages; 69% of participants reported spinal pain, and 38% complained of back pain.

What Graham and his colleagues hope people take away from the research is that these lengthy water collection times have real impacts on individual lives — typically, the lives of women and girls — and it’s important that they’re considered when measuring progress in access to safe water.