The winning blog entry for the 2019 Trinity College Dublin Development Issues Blog Series is Moya McDermott on the true cost of fast fashion indulgences and #influencers

There is a new force of work fuelling rapid consumerism on a massive scale – social media. According to a study from 2018, Instagram has over one billion active monthly users – and is now quickly approaching its’ second. An integral part of our modern lives, it is no wonder that brands have recognised a unique opportunity in using platforms like Instagram to market to the millions. The use of social media influencers to market products has exploded exponentially.

And it’s an effective method. Consumers admire and trust the influencers they follow, and brands take advantage of this. It has been found that 74% of people trust online product recommendations. The problem is that the people we are following and trusting advertise completely unrealistic lives. Consuming their content on daily basis and you will find yourself believing it is completely reasonable to need eight new outfit options for your weekend getaway. What’s more, recent marketing features on Instagram allow us act on impulse immediately – ‘swipe up’ on an influencer’s story and the product they are advertising could be yours in a matter of seconds. We are living in a new consumer age – buying 60% more than we were in 2000.

The reality is that most of the brands these influencers work with are fast fashion brands. Fast fashion brings the latest trends to the high street as quickly as possible, essentially the mass production of low cost, trendy clothing. Fashion Nova is an excellent example of this.

Known for capitalising on influencer advertising since its conception, they now have over 16 million followers and introduce an eye-watering 600-900 new designs each week. The brand has even been caught in hot water for producing Kim K inspired pieces before Kim herself

has had the chance to debut the real-deal designer piece. To add some context – as recently as the 1990s, most fashion labels put out two main collections per year.

With the influencer marketing industry expected to reach a value of $10 billion by 2020, this digital marketplace is only going from strength to strength – and it’s vital that we take a step back and analyse the detrimental effects it is having on global sustainable development.

The True Cost of our Fast Fashion Indulgences

Widespread globalisation has made it easy for companies to outsource the bulk of their production to developing countries such and Bangladesh or India, with lax regulations and low labour costs. A massive source of both environmental and human rights issues, fast fashion is certainly up to Sustainable Development Goal standards. Here is a quick run through of the main issues.

- The industry is one of the largest polluters on earth, coming second only to oil.

- The cheap nature of clothing also makes it one of the largest sources of waste on the planet. 3/5 garments made in 2018 will end up in landfill before the year is out.

- The toxic chemicals used in production end up affecting the environment the workers live in the most by leaking into nearby water supplies. It is said that in China you can predict the trends of next season by the colour of the river that flows nearby a factory.

- A lot of power is used to sustain these large-scale factories. The UN states that the fashion industry consumes more energy than the aviation and shipping industry combined. To make it worse – the developing countries in which are they are based almost all depend on coal power.

- It would take 13 years to drink the water needed to make one T-shirt and a pair of jeans. Countries producing these, like India and Bangladesh, are suffering from water scarcity.

- 80% of the estimated 40-60 million workers are female. Although the apparel industry is the largest employer of women globally, less than 2 percent of those women actually earn a living wage.

- Suppliers meet high demand while keeping profits by forcing eighteen hour days while not even paying overtime.

- Thousands of workers have died in sweatshop conditions from fires and hazardous conditions to heat exhaustion and roof collapses.

In a Netflix documentary called ‘The True Cost’ a female worker is quoted “these clothes were made with our blood.” The statement echoes the amount of human suffering that fuels our need to shop.

Is there light at the end of the fast fashion tunnel?

If Instagram stars can influence us to indulge in an industry that is so damaging, surely the logic would follow that they have the power to lead their followers down a more ethical road. Although it might sound like a tough task to go from advertising Kim Kardashian knock-offs to second hand glam – I believe it could be done. We’ve seen how the plastic free trends of keep cups and metal straws achieved massive success. Switching from fast-fashion to more sustainable methods may require more of a committed lifestyle change, but young people of today are more environmentally conscious then they ever have been before. If a perfect time for change exists, it would seem to be right now.

For now, follow these sustainable fashion friendly Irish influencers to give your feed an eco-friendly makeover.

- Featured photo by Bruno Candeias, Jan 12th 2016 via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)

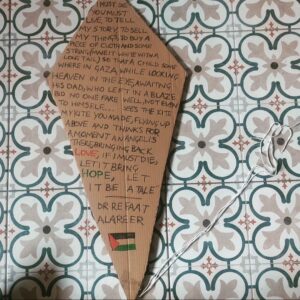

Urgently needed and timely new resource from Afri

Ciara Regan reviews Afri’s latest resource, Sowing Seeds of Peace, for post primary teachers which is adaptable and immediately useful across a range of school subjects.

It’s international women’s day. Don’t forget to tag us now that you feel #prettypowerful

From getting out to vote and entertaining two children off school due to it being a make-shift polling station, Ciara Regan reflects on international women’s day 2024.

Punching above its weight

Juan Acevedo-Ossa explores South Africa’s case against Israel as the latest example of its ability to act as a normative superpower, exceeding the great powers in shaping global moral discourse.

Empathy in a Divided World – workshop

Join us for this online session Empathy in a Divided World led by Brighid Golden to discuss how educators can respond to the challenges of selective empathy, both for ourselves personally and with others in our different settings.

What does Palestine have to do with Africa?

How does Israel’s current aggression on Gaza relate to Africa’s own history of political violence in Uganda and Africa?

‘What life is this?’: Escaping Ukraine’s occupied territories

From food shortages to informants, eight evacuees talk about life in Russian-occupied towns