- Feminism by Jay McNally via Flickr used under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

As educators (in whatever context you are in), how do you challenge misogyny, when facts are no longer sacred, and challenge popular opinion? Ciara Regan explores the issues on International Women’s Day.

Time and time again, in conversations with teachers, youth workers, educators in ANY context, the current issue of concern in day-to-day interactions with learners is misogyny. It can (and should!) be argued that it has long been a part of our everyday interactions, however, this current ‘strain’ or ‘variant’, if you like, of misogyny is particularly insidious.

If we go back as far as when the term misogyny first emerged, it was in the 17th century in response to an anti-women pamphlet: ‘The Arraignment of lewd, idle, froward and unconstant women’, written, printed and distributed by and English fencing master called Joseph Swetnam, at a time when debates about women’s place in society were happening. In the pamphlet, Swetnam discusses the sinful, deceiving and worthless nature of women, and includes what would be referred to now as sexist jokes. His target audience? ‘the ordinary set of giddy-headed young men’ and it was extremely popular. Any of this sounding familiar yet?

It wasn’t until second wave feminism in the 1970s that the use of the word misogyny became much more widespread, thanks to Andrea Dworkin’s book ‘Women Hating’:

‘The core of this book is an analysis of sexism (that system of male dominance), what it is, and how it operates on us and in us.’

Her writing is an extremely raw look at the systematic biases affecting the everyday experiences of women – much like Laura Bates and her Everyday Sexism project, and subsequent books.

But why does this matter, you might ask? Where misogyny emerged from or when it was first coined? It is important to remember, misogyny is nothing new. Every wave of feminism has had to face it in it’s various forms and guises, be they pamphlets in the 1600s, systems of male dominance in the 1970s, or patriarchal structures within the family unit.

It is a familiar beast and while it is not new, one thing has changed, however, and that is how it is being delivered to young people – young men, in particular.

It has become so ubiquitous on social media, with the algorithms forever in its favour. This is where it is particularly insidious, especially for those who are in the process of trying to figure out who they are in the world.

Mariead Moloney, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Kentucky who studies online misogyny, states:

‘It’s really seductive for someone like Andrew Tate to come along with a worldview that puts you at the very centre of the world and, in essence, makes all other groups beholden to you’.

I have spent time reading and researching about how to respond to the challenge of misogyny in its current online form and have come away wanting. Other than demands for better education from younger ages on these issues, better relationship and sexual education for children in school, encouraging these conversations from younger ages to demystify these issues and to allow our young people a safe space to ask difficult questions to help foster better understanding (all of which are valid and essential responses), it doesn’t do much to address the immediacy faced by those dealing with this variant of misogyny day to day, either from classmates, students or colleagues.

As educators (in whatever context you are in), how do you challenge these ideas, when facts are no longer seen as such, especially if they go against the beliefs or opinions being shared, such as those above? Are facts still sacred when the lines between fact, fiction and belief have become so blurred in an age of ‘alternative facts’?

As the title of this piece goes, I don’t know what the answer is, but we need to keep having these conversations.

Misogyny is all about power

Australian feminist author, Clementine Ford argues that at its very core, misogyny is all about power. Claiming power at the expense of the collective whole. Ford argues that we need to continuously keep counteracting the messages of these men (Tate and his ilk) online, we must keep disrupting these messages that are so appealing to young men, instructing them about how they are being disenfranchised by feminism and disempowered by women’s equality (despite evidence to the contrary). And keep disrupting most especially when met with resistance.

Experiences young men are having (young women too, are equally susceptible to misogynistic messaging), feelings of disempowerment, are a function of being human; all young people share these feelings at some point in their lives. This is not because their power has been ‘stolen’ from them and in order to regain, they need to participate in the age old practice of misogyny – again, claiming power at the expense of the collective whole.

This is where we need to use that incredibly valuable safe space for conversation to explore the idea of power and what that means, where does their power come from?

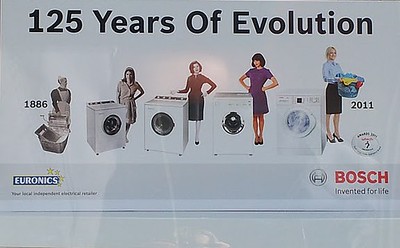

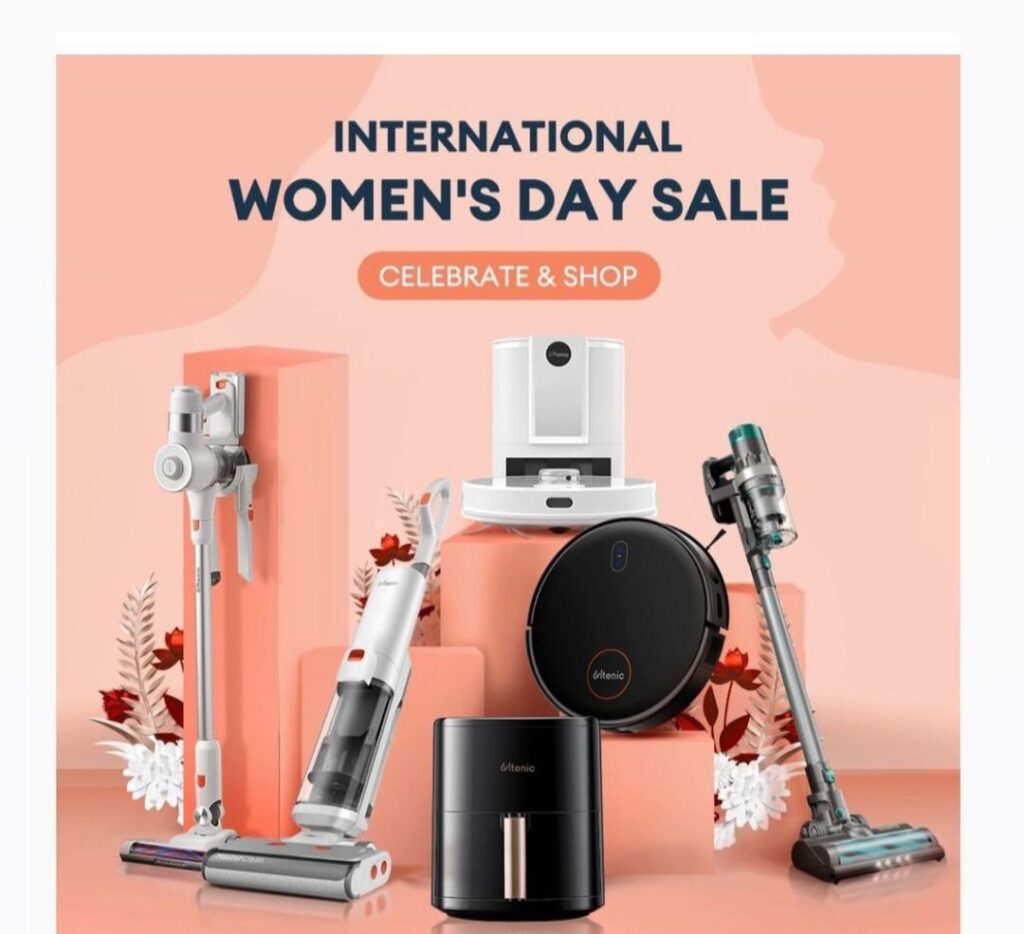

Today is International Women’s Day, and just like last year, I am (even more) fed up of the capitalist co-opting of what was once an incredibly important day of acknowledgement and celebration of the progress of women’s rights. As time ticks by, it can sometimes feel there is less and less to celebrate as we stand in solidarity with our sisters around the world.

Again, I ask myself, what do I do in response to all of this?

Still, my answer is, I don’t know. But what I do know is this: that I can’t do nothing. To go back to Clementine Ford’s points about power, we need to be having those difficult conversations about power, masculinity and what that means to young men.

That they have the power to shape what that means for them, they just need to exercise it within themselves, that it hasn’t been stolen by anyone, or that to gain control of your power does not need to be at the expense of others. These conversations are happening anyway, usually online and usually with the likes of Tate. We need to insert ourselves into these conversations, to speak to them and to counter those messages.

If you wish to celebrate the women in your life (I know I do, but that much is obvious), then don’t buy them the flowers you’re being told you SHOULD be on IWD, or a pair of fluffy pyjamas, commit to having those difficult conversations, to this life long project of challenging these ideas around power at the expense of others and disrupt. Even if we don’t have the answers – perhaps ESPECIALLY when we don’t have the answers. This space is a safe one for these conversations and I invite you, reader, to participate. To disrupt.

6 starter resources for educators

Women’s rights quiz – take the test

Facts Matter is an introductory guide for adult literacy and adult education practitioners on critical thinking, media and digital literacy.

Free speech, censorship and snowflakes – take the quiz

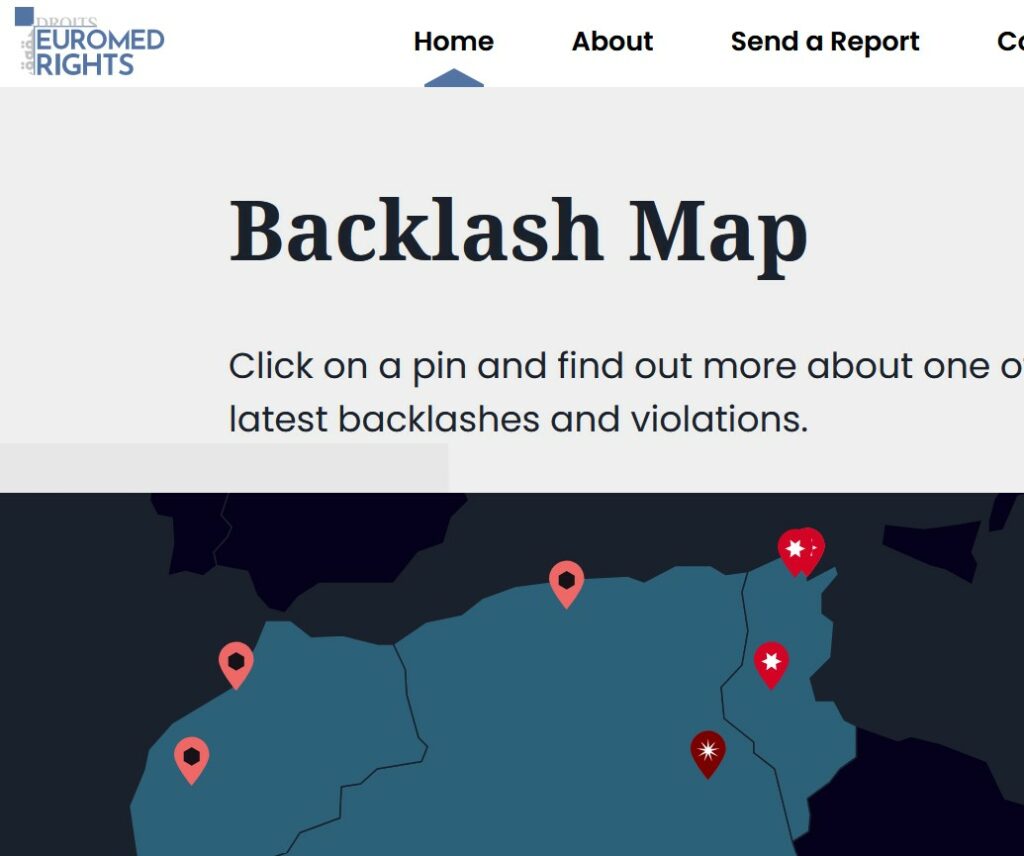

EuroMed Rights’ interactive Backlashes Map aims to document attempted and successful forms of contestations/ ‘backlashes’ to gender equality and women’s rights in the Middle East and North Africa.

Through the Looking Glass: a guide to empower young people to become advocates for gender equality by the National Women’s Council of Ireland

More on developmenteducation.ie

It’s international women’s day. Don’t forget to tag us now that you feel #prettypowerful

From getting out to vote and entertaining two children off school due to it being a make-shift polling station, Ciara Regan reflects on international women’s day 2024.

I don’t know what the answer is, but we need to keep having these conversations

As educators (in whatever context you are in), how do you challenge misogyny, when facts are no longer sacred, and challenge popular opinion? Ciara reflects on International Women’s Day

#100objects podcast: ‘For many people, it’s not questioned’ – on FGM and women’s rights in Kenya with Órla Ryan

Órla talks about what it was like meeting former circumcisers involved in female genital mutilation, the power of her platform working in a newsroom, her views on the term ‘fake news’ and shares tips for young people (particularly women) interested in exploring roles in journalism.

Let’s talk about the Amber Heard v Johnny Depp trial

2 actors, one trial and a Billion hashtags. What happens when the media gets a hold of a woman on trial? This blog takes a look at the reaction to the Heard v Depp trial and what it reveals about women’s representation.

#100objects: Órla Ryan on Female Genital Mutilation and women’s rights in Kenya

Órla Ryan reflects on her assignment in Kenya in April 2019 examining women’s rights issues, in particular female genital mutilation (FGM) and gender-based violence at the launch of the Irish Global Solidarity in 100 Objects exhibition.

Women’s rights quiz -take the test

Take the quiz and test your knowledge, based on the 10 Myths About Women’s Rights myth buster.