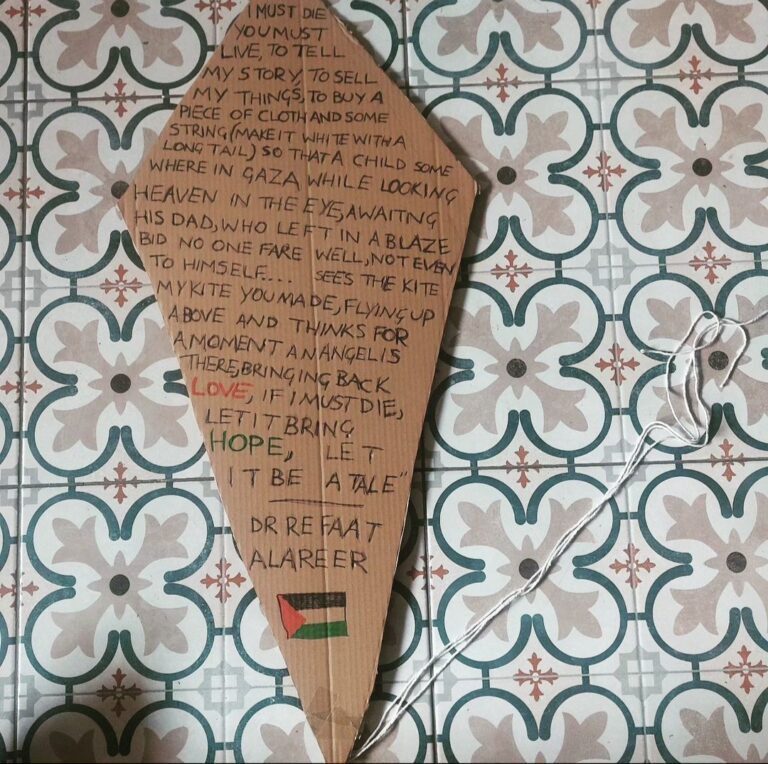

Indian farmers protest against the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Indian government imposed strict crackdowns on protestors and critics. Photo by Randeep Maddoke via Wikimedia Commons.

This UN report can teach us a lot about protecting civil society space during a crisis. Kai Evans provides a summary.

COVID-19 restrictions were undoubtedly vital in stopping the spread of the virus and protecting public health, and in particular, the most vulnerable members of society. However, the COVID-19 pandemic was also used by governments to suppress dissent, limit human rights and stifle the civil society space.

In light of this, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) prepared, at the request of the Human Rights Council, a report titled ‘Civil society space: COVID-19: the road to recovery and the essential role of civil society’ to examine the challenges faced by civil society during the pandemic. Following analysis of inputs from nations and civil society, as well as independent research, the OHCHR concluded that there were five key lessons learnt during the COVID-19 pandemic, in the context of protecting the civil society space.

Let’s summarise them here:

1. ‘Participation in decision-making decreased and became less safe and inclusive.’

This came as a result of online means of communication being inaccessible to many communities, particularly the poorest and most often excluded groups. For example, older people, indigenous people, women and people in rural areas had increased barriers to participation. In addition, the expansion or creation of restrictions offline meant critical voices were increasingly affected by censorship, surveillance and persecution.

2. ‘Interference with the flow of information was recorded around the globe.’

This was invariably done with the stated aim of countering disinformation or controlling information about the pandemic. There were numerous laws around the globe which restricted freedom of expression and were in violation of international human rights law. Detention and imprisonment for criticising ‘COVID-related government measures’ or for questioning the accuracy of official information was commonplace.

3. ‘Dialogues and exchanges with people and communities, particularly those at risk of being left behind, are key to countering disinformation and fostering trust.’

Civil society representatives, such as journalists, protesters and human rights defenders, were shown to be critical sources of information and feedback that enable governments to enact and implement policies that are effective, sustainable and gender-responsive. When these channels of dialogue were closed during the pandemic, disinformation spread. This, in turn, has a negative impact on levels of interpersonal trust and institutional trust, which has already been in steep decline for decades.

4. ‘Transparency with regard to any interventions with freedoms and access to information for all people and communities is critical for overcoming [a health crisis].’

Measures such as limiting media independence, suppressing debate, censoring content and banning protests are ‘likely to amplify the negative effects of a health crisis, can sometimes even lead to loss of life and can undermine the effectiveness of measures taken to combat the pandemic.’ At a time when coordination and cooperation is vital to overcome the worst effects of the pandemic, particularly vaccine inequality, this is a worrying find. If basic human freedoms are not respected, the chances of an effective response to the pandemic are reduced.

5. ‘The recipe for effective crisis response and for trust…is a more systematic investment in…safe and inclusive participation at all levels…effective measures to protect access to information…an enabling environment for debate [and] the security and holistic protection of those who speak up.’

The UN Secretary-General has recognised trust as critical for building resilient societies and for sustainable development and peace. In order to combat any crisis, health or otherwise, it is important that trust in institutions, such as the government, health authorities and an independent media, is maintained and fostered. This allows for greater and more effective cooperation and transparency. However, when participation in civil society is hampered, either through inaccessibility, censorship or persecution, trust levels remain low, while the crisis response can be limited in its effectiveness.