What The Fact?

Photo: Chevron sign. Photo by Roo Reynolds via Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)

Chevron claims that they achieved their target of lowering carbon intensity between 2016 and 2020, but is this really helping to lower emissions? Kai Evans reviews the evidence.

The Claim

In July 2022, the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) ended their involvement with the Texaco Children’s Art Competition, which has been a hugely popular competition in Ireland for over 60 years. This is as a result of campaigners such as Tom Roche and environmental writer John Gibbons (since 2017) highlighting issues surrounding Texaco’s fossil fuel usage, catastrophic environmental damage (such as in Ecuador) and using the competition as ‘artwashing’, or attempting to improve the company’s reputation in Ireland through supporting the arts.

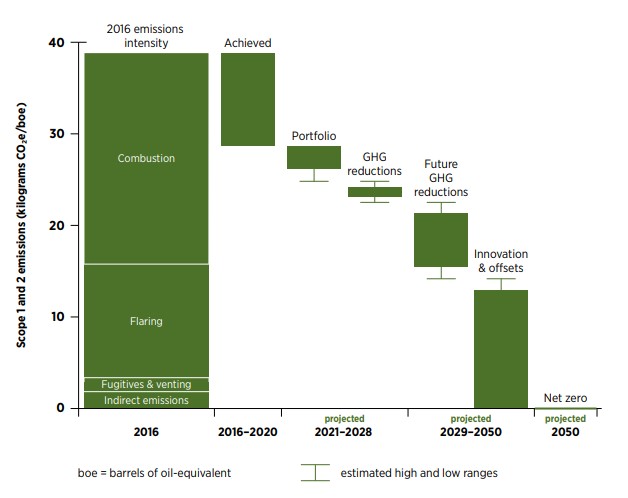

Chevron (who bought Texaco in 2000 and Valero Energy in 2011) claim that they achieved their target of lowering carbon intensity between 2016 and 2020 (i.e. they reduced their level of carbon intensity by a little over 10 kilograms CO2e/boe for Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions) in their 2021 corporate sustainability report.

And yet, on 13th June this year, Chevron claim:

“As part of a larger effort to help meet rising energy demand and lower carbon emissions, we are increasing production in the Permian Basin by over 15%”

Are activities such as this just a form of greenwashing, where large corporations or governments make pledges with regards to the climate, but rarely back these up with meaningful action?

The Verdict

The claim is rated misleading (elements of the claim are accurate, but presented in a way that is misleading) based on the best evidence publicly available at this time.

Chevron did seemingly meet their lower carbon intensity targets for 2016-2020 for Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, but it is presented in such a way that their actions are having a positive impact on global emissions, which is not entirely accurate.

In reality, this means little, as Chevron have actually increased their hydrocarbon production and total emissions over the same period.

The Evidence

To look under the hood of pledges, actions and evidence, it’s important we understand the language and ideas used by companies when they publish reports and make public ‘sustainability’ declarations.

To this end, we need to look at three key ideas: ‘carbon intensity’, ‘scope emissions’ and ‘greenwashing’.

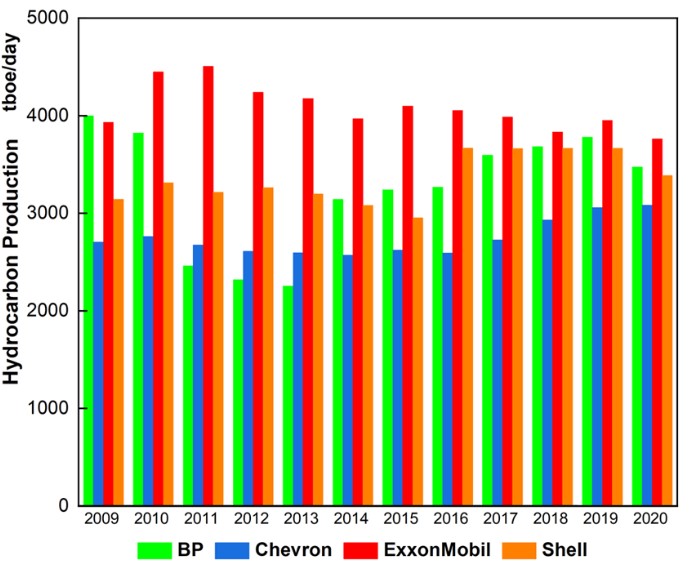

While Chevron reduced their carbon intensity levels in the period 2016-2020, they have also been increasing hydrocarbon (oil and gas) production since 2009, and indeed since 2016, as shown in a recent a study in February by researchers Jusen Asuka, Mei Li and Gregory Trencher from Tohoku University and Kyoto University.

Hydrocarbon production is often considered a reliable indicator of overall greenhouse gas emissions, as hydrocarbons are the principal components of petroleum and natural gas.

What is greenwashing?

Greenwashing, or greenwash, as the Oxford Dictionary states, is

‘disinformation disseminated by an organization so as to present an environmentally responsible public image’.

There are countless examples of this practice, but here’s a brief selection:

- Ryanair claiming in adverts (which were promptly banned) that they are ‘Europe’s lowest emissions airline’ with little to no evidence.

- McDonald’s introduction of paper straws, which were found to be non-recyclable.

- H&M’s sustainable fashion claims, which the Changing Markets Foundation found to be false a whopping 96% of the time (compared to an already abysmal 60% average for the rest of the fast fashion industry).

We need to talk about 'Scope emissions'

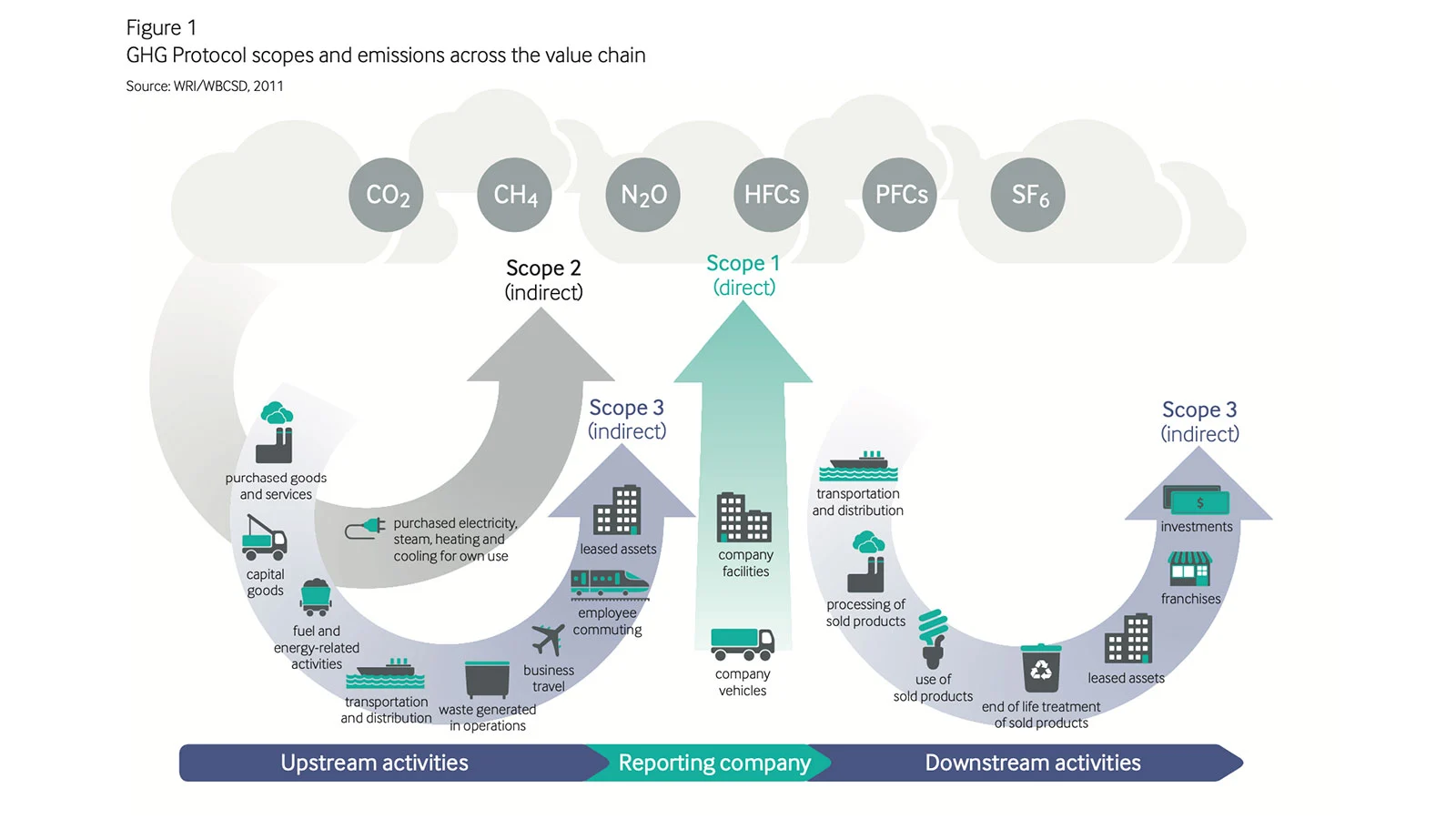

The Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHGP) is a global, standardized framework for measuring and managing emissions from private and public sector operations, value chains, products, cities and policies to enable greenhouse gas reductions and mitigation actions. The initiative was established and led by the World Resources Institute (WRI) and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD).

The Protocol makes reporting Scope 1 and 2 emissions mandatory, but Scope 3 emissions are voluntarily reported. As a result, many companies exclude these from their targets and data. But what are Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions?

- Scope 1 emissions are also known as direct emissions. In other words, these are emissions from company owned or company controlled resources. These include factory fumes, emissions from company owned vehicles, air conditioning units, heating and so on.

- Scope 2 emissions can be described as indirect emissions – owned. These are almost always from purchasing energy from a utility provider. For most firms, electricity consumption is the dominant source of Scope 2 emissions.

- Finally, Scope 3 emissions refer to indirect emissions – not owned. There are 15 categories of these under GHG Protocol, but some of the most important include business travel, employee commuting, product transport and manufacturing, waste generation, franchises’ emissions and actual production of goods bought by the company, such as food or stationary.

Scope 3 emissions, while generally not reported, make up, by far, the largest share of a company’s emissions. For example, Apple’s Scope 3 emissions account for over 98% of their total emissions.

Only reporting Scope 1 and 2 emissions, as Chevron has up until 2018, is therefore really relatively meaningless in the broader context of the climate crisis. The addition of Scope 3 reports in the last 2 years and the subsequent push by shareholders at the AGM in May 2021 in for a proposal to reduce Scope 3 emissions has placed management in a tricky position, who opposed the proposal.

As a follow on, Chevron set a target in October 2021 to reduce the carbon intensity of its products (Scope 3) by 5% by 2028. To place this in context, here is the response from the green shareholder group Follow This that led the resolution at the AGM:

“Chevron is merely interested in appeasing shareholders, a 5% intensity target is a snub to investors who are truly committed to reaching the Paris agreement,” said Mark van Baal, founder of shareholder group Follow This that filed the climate resolution at Chevron.

The scientific consensus is clear: the world needs to reduce absolute emission by around 40% by 2030 to have any chance to achieve the Paris Accord. Until Chevron’s targets reflect this fact, their strategy falls short of Paris-alignment. 5% is disappointing tokenism, not a serious attempt to confront the climate crisis.”

More detailed info on the different scopes, categories and their importance can be found from the Plan A Academy.

A note on the problem with 'lower carbon intensity'

Lowering carbon intensity is important to tackle the climate crisis, but only if we also reduce total emissions. The carbon intensity value in Chevron’s case is the kilograms of carbon dioxide (or equivalent – methane, for example) (CO2e) produced per barrel of oil (or equivalent – natural gas, for example) (BOE) produced.

Chevron’s (and most other companies) carbon intensity has fallen due to becoming more efficient extracting fossil fuels. For example, they may use electric vehicles to transport people and equipment, or perhaps solar powered pumps, or they might use energy efficient lightbulbs, or some of their electricity is sourced renewably (via wind or solar energy) by their utility provider. These are just basic examples, but it is easy to see how this would lower what’s known as ‘Scope 1’ and ‘Scope 2’ emissions, and the carbon intensity per barrel of oil.

However, this does not take into account ‘Scope 3’ emissions, continued production and exploration of oil and gas, or the actual use of the fossil fuels which they extract and sell to the world. So while they may be more efficient per unit of fossil fuel they produce, it’s not actually reducing global emissions – it’s actually increasing them!

More on CO2e can be found here, BOE here and carbon intensity here.

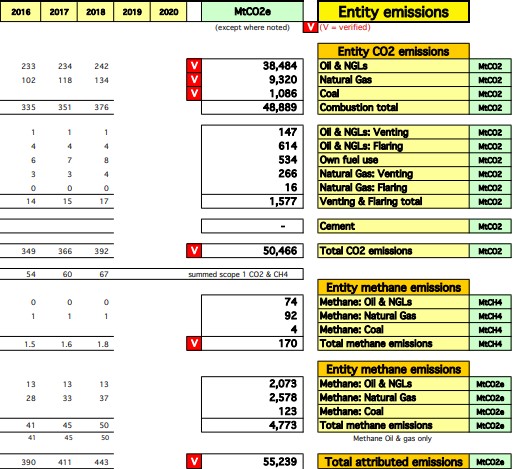

The Climate Accountability Institute have also calculated Chevron’s total greenhouse gas emissions. Their most recently available report from 2020 has data up until 2018.

On this basis, between 2016 and 2018, Chevron clearly increased CO2 emissions, methane emissions, and total emissions, as shown below.

Pledges and actions under the microscope

While Chevron’s carbon intensity levels have fallen, their total emissions and hydrocarbon production have increased in the last 10 years.

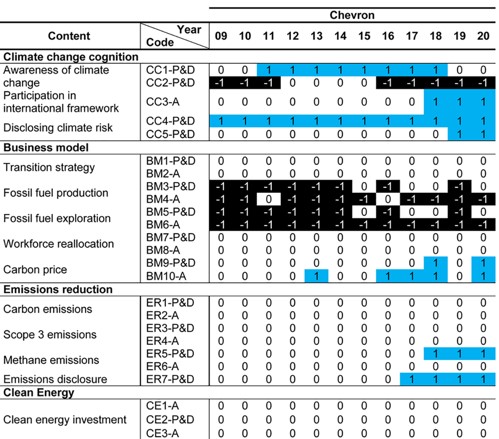

Li, Trencher and Asuka’s recent study focuses on two American (Chevron, ExxonMobil) and two European major companies (BP, Shell). Using data collected over 2009–2020, the research team examined the extent of decarbonization and clean energy transition activity from three perspectives: (1) keyword use in annual reports (discourse); (2) business strategies (pledges and actions); and (3) production, expenditures and earnings for fossil fuels along with investments in clean energy (investments).

Reading the data:

- ‘0’ indicates no action,

- ‘1’ indicates pledges and actions which reinforce or implement a strategy or commitment made that year, while

- ‘-1’ indicates negative pledges and actions which contradict or hamper a strategy or commitment made that year.

- P&D refers to ‘pledges and discourse’ while A refers to ‘actions’.

As we can see, while Chevron have improved in areas around disclosing climate risk, climate change awareness and more recently, carbon pricing and emissions disclosure, Chevron have said or done little else positive, yet have continued to substantially increase fossil fuel production and exploration.

The focus of the ‘clean energy claims’ study on Chevron, ExxonMobil, BP and Shell is conclusive:

The financial analysis reveals a continuing business model dependence on fossil fuels along with insignificant and opaque spending on clean energy. We thus conclude that the transition to clean energy business models is not occurring, since the magnitude of investments and actions does not match discourse. Until actions and investment behavior are brought into alignment with discourse, accusations of greenwashing appear well-founded.

As explained in a Guardian report, this further confirms what many have said for years: ‘oil companies are largely all talk and no action.’

Chevron's reply to 'greenwashing' claims

Video: Chevron ad from 2021 explaining “We’re lowering the carbon emissions intensity of our operations, investing in lower carbon technologies, and exploring renewable fuels of the future.”

Chevron’s typical response to ‘greenwashing’ claims generally follows a standard company line. In March 2021, Greenpeace, Global Witness and Earthworks filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission in the USA on Chevron’s greenwashing tactics and misrepresentation of the public.

This complaint focused on ad campaigns and Chevron’s claims of ‘ever-cleaner energy’ despite increasing emissions, implying that their work is not harmful to the environment and for using jargon such as ’emissions intensity’.

Chevron’s response was predictable, calling the accusations ‘frivolous’ while spokesperson Sean Comey said the following:

‘We are taking action to reduce the carbon intensity of our operations and assets, increase the use of renewables and offsets in support of our business and invest in low-carbon technologies to enable commercial solutions.’

Chevron/Texaco’s responses to well-documented challenges over many years has led to them being accused of legal intimidation and an aggressive defensive style, such as in the Ecuadorian “Amazon Chernobyl” case. Deep in the Amazon rainforest of Ecuador, Texaco (later owned by Chevron) reportedly dumped 72bn litres of toxic oil waste, allegedly causing high levels of cancer and other illnesses for the indigenous people. This is a serious cause for concern and should be widely known.

- One of the key activists and lawyers for the case, Steven Donziger, was kept under house arrest for 993 days until April of this year, most of which was pre-trial detention.

- In the words of one Chevron official: “We will fight this until hell freezes over, and then fight it on the ice.”

- Numerous human rights groups, legal associations and even the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights have supported Donziger and/or heavily criticised Chevron’s legal tactics in this decades-long, extremely complex case.

Questions about access to justice and access to remedy are important. Corporations can counter-sue their accusers, crushing any opposition under, to use Chevron’s words, “an avalanche of paper”. Environmental advocate Erin Brockovich noted in The Guardian in February 2022:

“This is part of a disturbing legal playbook sometimes known as Slapp – strategic lawsuit against public participation. Massive corporations can fund endless litigation against activists or critics. They don’t even need to win in court, because they can intimidate or bankrupt their opponents in legal fees.”

Conclusion

In 1998, Chevron, ExxonMobil, utility companies and the American Petroleum Institute signed up to the Action Plan, which stated that ‘victory will be achieved when average citizens’ and the ‘media ‘understands’ (recognizes) uncertainties in climate science’.

Chevron (and many other energy companies) attempting to mislead the public is not a new phenomenon.

- Chevron have indeed met their lower carbon intensity targets for 2016-2020 as claimed, but this has been framed as something which significantly addresses the climate crisis and the transition towards a greener future.

- In reality, this means little, as Chevron have actually increased their hydrocarbon production and total emissions over the same period.

- Therefore, it can be said that their performance from 2016-2020 to lower carbon intensity levels is a clear example of greenwashing. This is particularly concerning as they seem to be committed to using lowering carbon intensity levels in their Scope 1 and 2 emissions as their primary goal in addressing the climate crisis going forward.

- In terms of the Texaco Art Competition within the competition’s rules, Texaco state that ‘all entries shall be the property of Valero Energy (Ireland) Limited, who shall also be the owner of the copyright’ and ‘all entries together with the artists’ details may be used in publicity campaigns’. Questioning the ownership of the original artwork and use of a national competition to further the marketing and brand profiling of a fossil fuel energy company must be called into question. For more on this link with the Texaco Art Competition, see Tom Roche, Colm Regan and Peadar King’s article in the Offaly Express and the sports and Chevron-Texaco story by Tom Roche in 2021.

Verdict

Based on the What The Fact? scales guide, the claim is rated as Misleading – elements of the claim are accurate, but presented in a way that is misleading – based on the best evidence publicly available at this time.

- Kai Evans is a masters graduate in International Development, and a contributing writer with developmenteducation.ie

developmenteducation.ie’s What The Fact? supports the code of principles of the International Fact Checking Network. We check claims by influencers, from local to national to transnational that relate to human rights and international human development.

Transparent fact checking is a powerful instrument of accountability, and we need your help. Send tips and ideas to facts@developmenteducation.ie

Join the conversation #whatDEfact on Twitter @DevEdIreland and Facebook @DevEdIreland

More on developmenteducation.ie

Urgently needed and timely new resource from Afri

Ciara Regan reviews Afri’s latest resource, Sowing Seeds of Peace, for post primary teachers which is adaptable and immediately useful across a range of school subjects.

It’s international women’s day. Don’t forget to tag us now that you feel #prettypowerful

From getting out to vote and entertaining two children off school due to it being a make-shift polling station, Ciara Regan reflects on international women’s day 2024.

Punching above its weight

Juan Acevedo-Ossa explores South Africa’s case against Israel as the latest example of its ability to act as a normative superpower, exceeding the great powers in shaping global moral discourse.

Empathy in a Divided World – workshop

Join us for this online session Empathy in a Divided World led by Brighid Golden to discuss how educators can respond to the challenges of selective empathy, both for ourselves personally and with others in our different settings.

What does Palestine have to do with Africa?

How does Israel’s current aggression on Gaza relate to Africa’s own history of political violence in Uganda and Africa?

‘What life is this?’: Escaping Ukraine’s occupied territories

From food shortages to informants, eight evacuees talk about life in Russian-occupied towns