Practice Empathy. Photo by Quinn Dombrowski via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

This teaching unit has been developed to support teachers and students in learning about and critically engaging with the concept of empathy but more specifically, selective empathy.

The teaching unit is recommended to teachers of the following senior primary and Junior cycle subjects:

- SESE (SP): Geography (human environment), History (skills and concepts development).

- SPHE (SP): Myself and my family, Myself and the wider world, Myself and others

- The Arts Education (SP): Contribution to a sense of personal identity.

- SPHE (JC): Strand one: understanding myself and others (1.8).

- CSPE (JC): Strand one: rights and responsibilities; Strand two:Global Citizenship Education

In an increasingly polarised world where conflict is abundant and compassion is sparse, connecting to and understanding one another is needed now more than ever.

Empathy is a term often presented as a universal good, the more caring and supportive cousin of sympathy. In the words of Brené Brown,

“empathy fuels connections while sympathy drives disconnection”.

Empathy forces us to connect with others, to consider their circumstances and attempt to understand how they are feeling in a situation by connecting those feelings with something inside ourselves. Whereas sympathy allows us to look at an issue purely as an outsider without requiring us to be vulnerable or connect to the feelings involved.

Online workshop

Register here and join us for an online workshop based on this teacher’s guide to tackling selective empathy in a changing and challenging world.

Join us for this online session Empathy in a Divided World led by Brighid Golden to discuss how educators can respond to the challenges of selective empathy, both for ourselves personally, and with others in our different settings.

Grab your lunch and join us online for a session of interest to teachers and educators in senior primary, Junior Cycle SPHE, CSPE and higher education as well as youth leaders and youth workers.

When: Thursday 25/01/2024

Time: 13:10 – 13:50 (40 minutes)

Registration: register your place (limited spaces via Zoom)

| Sympathy | Empathy | Selective Empathy |

|---|---|---|

| Sympathy can be described as feelings of pity, or sorrow for another person’s circumstances. | Empathy is the ability to understand, share, and connect with another person’s circumstances. | When our empathy is directed at just one person or group to the exclusion of others. This often occurs when our empathy is manipulated by our (sometimes) unconscious biases shaped by society, the media and our own misconceptions. |

Selective empathy is when our empathy becomes restricted to just one particular person or group of people above others. Usually, our selective empathy is focused on groups we belong to or people we feel a similarity with. Most of us naturally empathise abundantly with our families, friends, or immediate communities, but may find it difficult to empathise sincerely with people or groups outside of that.

Empathy requires emotional and mental labour, and this can be why we are selective in the empathy we naturally engage in as it is more difficult to empathise with people we do not immediately relate to.

Question: Where do we see sympathy and empathy in our everyday life (school, media, TV, books, family, interacting with strangers)?

Question: How do sympathy and empathy make us feel (when engaging with those feelings yourself or when they are directed at you)?

Question: How could we all work to bring more empathy than sympathy in our lives?

How does selective empathy happen?

Very few people engage deliberately in selective empathy, but instead become subconsciously swept up in populist narratives that play on their emotions or best intentions. Selective empathy can be actively cultivated through the media, through government messaging, and within our societies from groups with particular agendas.

In particular, the media can play a significant role in shaping the direction of the general public’s selective empathy by choosing which stories get heavy coverage and which get only a minor, easily lost, headline. Media outlets make choices about sharing and uplifting some voices while side-lining others. Essentially, the media ensures that the collective narrative is ‘zoomed in’ on a particular group or perspective, making it easy to develop empathy for them and difficult to consider any alternatives. Our subconscious is influenced by what we hear and see on an ongoing basis and it is difficult for individuals in a busy society to challenge that narrative alone.

Why Does Selective Empathy Happen?

Selective empathy is used to cause division between groups, to justify actions, or to push particular narratives. Some would argue selective empathy is not empathy at all and has been weaponised, particularly in contexts of conflict.

This has been evident across media platforms which have been used to push anti-migration rhetoric in the past number of years, sometimes by officials holding political offices, sometimes by groups with particular agendas. By tapping into people’s fears around safety and the cost-of-living crisis, groups have been able to drum-up support for a ‘nationalist vision’ which encourages people to prioritise the needs of people with the same ethnic or national identity as them. This ideology promotes selective empathy which places the concerns of Irish people above the suffering of others who may be fleeing war or other challenges.

Excerpts from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TED talk ‘The Danger of a Single Story’. The full version is also well worth checking out.

Additionally, tapping into people’s empathy has been used throughout history by leaders to justify and gain support for instigating war and conflict and causing harm to millions.

By encouraging people to have an empathetic approach to one particular group of victims, leaders have been able to manipulate the common narrative to prevent their citizens from considering the broader or longer-term impact of their chosen action.

In these instances, empathy is being weaponised by leaders wishing to go to war with the support of their citizens, and so they use empathy as a tool to incite hatred and anger against those they wish to invade or attack. Encouraging empathy for a particular group of victims energises people to want to strike out and instigate violence to protect the victims in the narrative being presented to them.

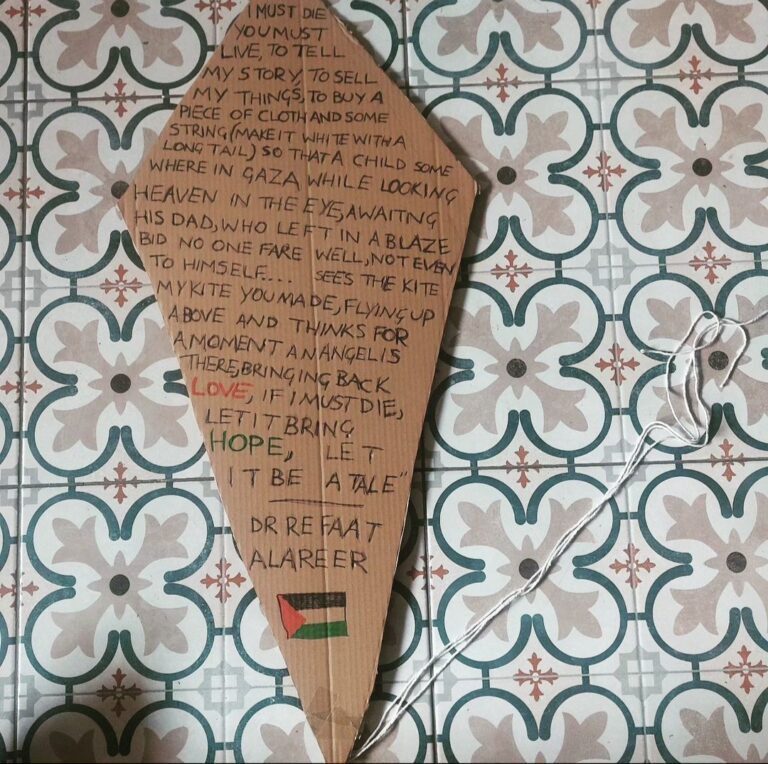

It is worth considering these ideas in light of recent conflict and in particular, to consider the ways in which empathy is being practiced, or possibly manipulated in relation to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. I encourage you to seek out spaces online or in person to encounter different voices and perspectives, and to notice where a broader context or consideration of others may be missing from certain perspectives.

To help with considering how empathy related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, read the following article from NPR in the US, which explores the question, Is There Any Empathy Left In The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict? While the article is from 2014, you might consider what, if anything, has changed since then.

Why should we be concerned about selective empathy?

By its very nature, selective empathy reinforces the concept of ‘othering’, potentially leading to dehumanisation.

By focusing our empathy on one group over another, we distance ourselves from people we consider to be ‘other’ and begin to think of groups of people as hierarchical, with some (usually those like us) considered more important than others.

Understanding selective empathy itself, how it is used, and the context in which it is being used, can give us a better understanding of people’s motivations or justifications for engaging with or supporting actions which go against basic justice or human rights values and principles.

The opposite of Othering is not “saming”, it is belonging. And belonging does not insist that we are all the same. It means we recognise and celebrate our differences, in a society where “we the people” includes all the people.

How to Respond

The most important habits for us all to develop are to stop and notice – pause and ask ourselves questions which will help us identify when the narratives we are hearing may be being manipulated. Some key questions that can help are:

Question: Who benefits from this story?

Question: Whose voice is missing from this story?

Question: - Would someone with a different identity or life experience than me have a different perspective on this?

An understanding of how and why this happens can support us in developing educational strategies to counteract the contexts which bring about selective empathy. By understanding that people have been ‘zoomed in’ on one particular group of victims, or potential victims, without an awareness or consideration of the broader historical or political context, helps in understanding why they might support violent action in the so-called ‘name of peace’.

How could I approach conversations around selective empathy in my setting?

Our educational approach to counteracting selective empathy should focus on disrupting the narratives that allow us to focus on just one group of people rather than taking a more global view of the issue at hand. Simultaneously, we must ensure that learners have the opportunity to broaden their knowledge and awareness of historical, political, and social contexts around issues where they may have employed selective empathy.

1 Andreotti and deSouza’s conceptual framework from ‘Learning to Read the World Through Other Eyes’ is a useful framework for disrupting selective empathy and encouraging us to broaden our narratives and consider other perspectives.

Learning to read the world through others eyes | |

Learn to Unlearn Deconstructing mainstream narratives and challenging personal perspectives as they are related to your own context (historically, culturally, politically, socially) Key question: Who wrote this? Where did this idea come from? Why do I think that? Is this information from a reliable source? | Learn to Listen Acknowledging the limitations of your own perspective. Taking in diverse perspectives, indigenous voices Key question: Who is missing? Who am I not considering? |

Learn to Learn Comparing and contrasting perspectives and ideas Key Question: How do my ideas/preconceptions differ from others? How can considering other’s perspectives benefit my own thinking? | Learn to reach out Self-reflection, shifts in thinking and what this might mean for your practice. Using your own learning in your practice. Key Question: How can I support others to question what they are hearing and consider alternative ideas? |

2 A focus on critical thinking in our educational spaces will support learners to question often taken-for-granted assumptions which lead to selective empathy.

One way to support critical thinking approaches is to consider it as inclusive of four key skills:

Developing your knowledge | Learning to question | Engage in self-reflection | Think about values |

Listen to multiple perspectives Make sure you are getting your information from trust-worthy sources | Start noticing and recognising where the stories being shared might be based on stereotypes Practice asking questions like ‘whose voice is missing?’ ‘who is benefitting from this story?’ before making up your mind | Take time to pause and reflect regularly, checking in with how stories are making you feel and whether they are making you feel connected or disconnected from people | Ask yourself if your actions match your values – for example, if you value equality, are you unintentionally excluding or othering another group of people Consider what values may be informing other peoples actions or the narratives they are pushing |

3 Counteracting the very idea of ‘othering’ people or groups who we do not feel or see an immediate connection with is necessary to challenge and disrupt selective empathy. This can be done through the use of compassion education through a resilience approach, like in the Educating the Heart programme, or a loving kindness approach.

Ultimately, in disrupting selective empathy, we must examine our motivations behind engaging in or supporting particular actions and challenge our unconscious biases.

Where that motivation connects to a charity-based approach to helping others and feeling instant reward for actions, there is a need to present more nuanced approaches to justice-oriented education which focuses on considering broader root-causes and historical, political, and social contexts of issues. A broader focus can help us to consider the true impact of an action and see the bigger picture denied by selective empathy.

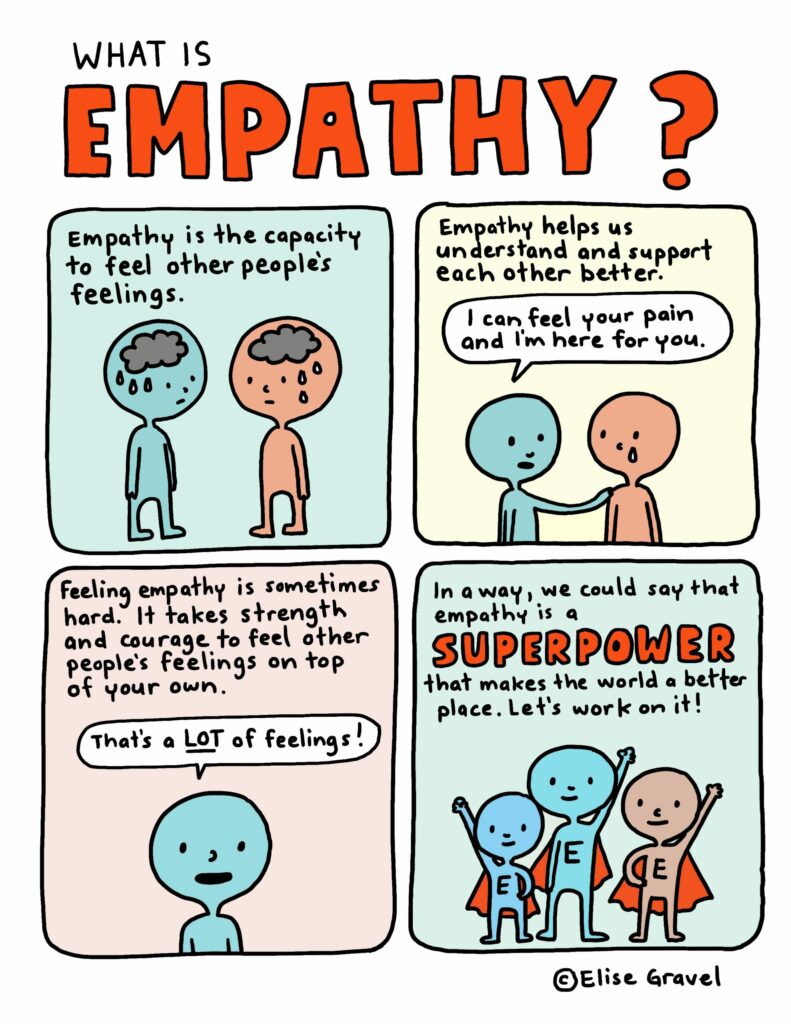

4 Lastly, take some time out to recharge your empathy muscles by looking for inspiration through creative outlets such as the video playlist below, or Elise Gravel’s cartoon on empathy (which is free to download from here). Share this exercise with learners and colleagues – it is a journey to be shared with others.

VIDEO PLAYLIST

Top 5 TED talks to nurture your empathy

Grace McManus shares her top recommendations to take some time out to recharge check out these 5 short videos that are bound to revitalise your empathy once again.

About the author

- Dr Brighid Golden is Assistant Professor in Global Citizenship Education at Mary Immaculate College, Limerick, working and teaching across undergraduate and postgraduate courses aimed at pre-service and practicing teachers. She is also a member of the DICE Network. Brighid teaches, researches, and publishes in the areas of global citizenship education, critical thinking, resource development, initial teacher education, and self-study research approaches.