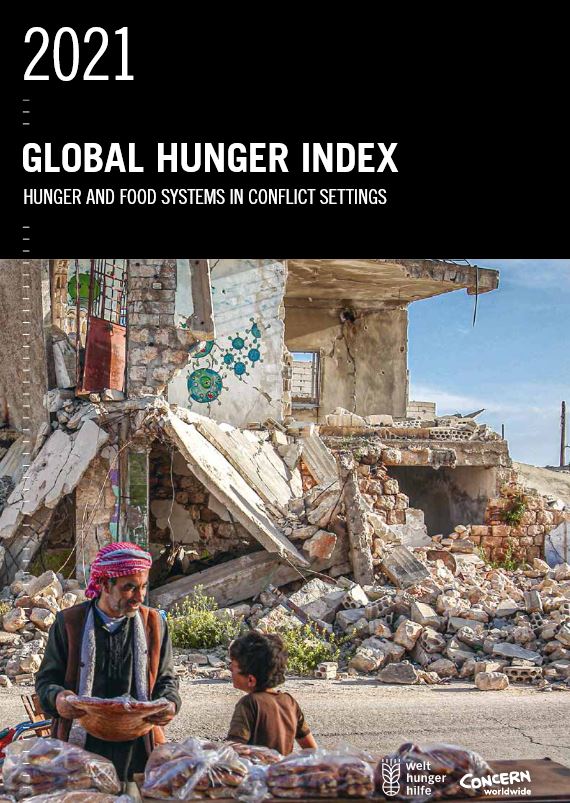

The opening line to the 2021 Global Hunger Index leaves no room for celebration or congratulatory back-slapping on progress to eradicate extreme hunger. With nine years to go, we are a third of the way down the international agenda to ‘leave no-one behind’ with some serious questions about scale, speed and urgency to be asked.

‘As the year 2030 draws closer, achievement of the world’s commitment to Zero Hunger is tragically distant. Current projections based on the Global Hunger Index (GHI) show that the world as a whole — and 47 countries in particular — will fail to achieve even low hunger by 2030.’

As World Food Day 2021 approaches, two flagship reports give us report cards on the last 12 months. Among the annual challenges of improving data collection to track and measure hunger, the COVID-19 pandemic has trampled on decades of incremental progress.

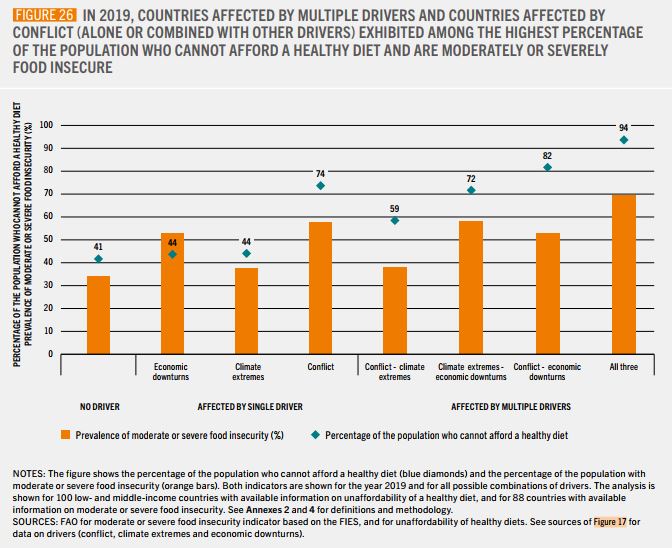

The multiplier effects of key drivers (not just a single driver) that exacerbate hunger are now tracked in more detail and are more visibly connected to the ongoing realities of global hunger. Climate-related disasters or climate extremes events, economic downturns/slowdowns, conflict and high-income inequality are drivers in the hot seat posing direct challenges to food security campaigns and interventions.

Global progress on tackling hunger is slowing, and hunger remains stubbornly high in some regions. How we are connected to this from Europe, by our actions and our inaction, matters.

As we look to grapple with this complexity, here are 15 graphics on trends and challenges from two key reports, the Global Hunger Index 2021: Hunger and Food Systems in Conflict Settings report by Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe (released today) and The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021 report by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the UN.

1.The shape of the Global Hunger Index map 2021, based on severity

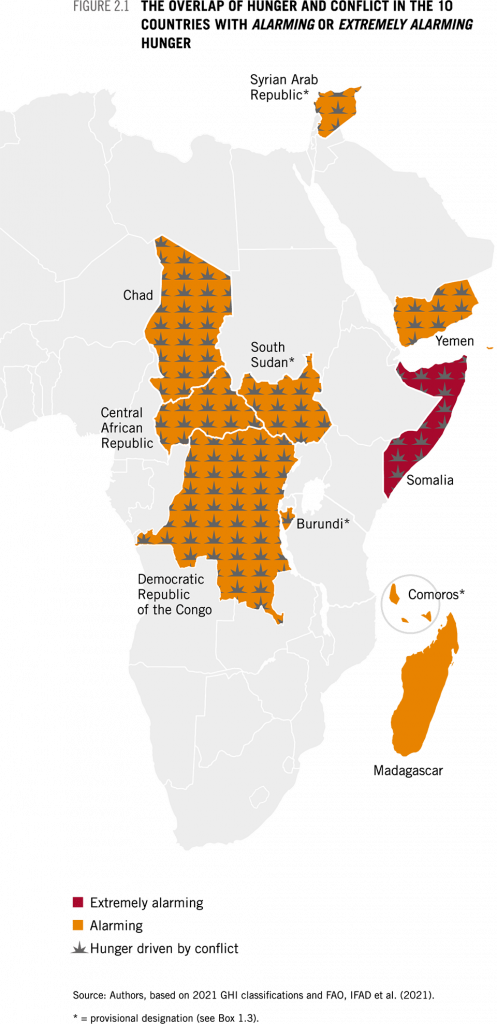

Dozens of countries suffer from severe hunger. According to the 2021 GHI scores, drawing on data from 2016–2020, hunger is considered extremely alarming in one country (Somalia), alarming in 9 countries, and serious in 37 countries.

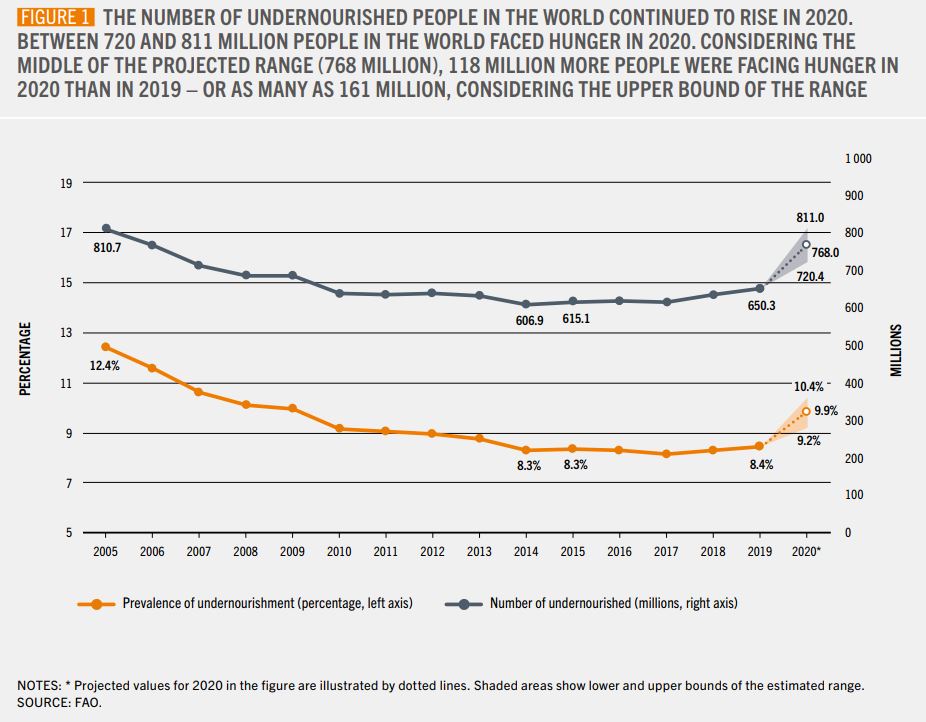

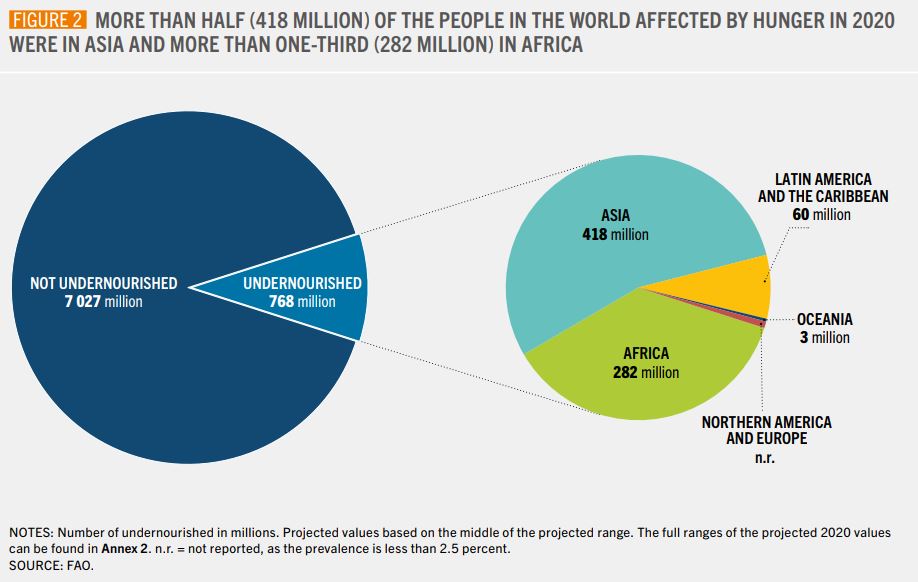

2.The number of undernourished people in the world continued to rise in 2020

3. Hunger overlaps with conflict in 8 out of the 10 'alarming' or 'extremely alarming' countries

4. The majority of 763 million (plus!) people in the world affected by hunger in 2020 were in Asia or Africa

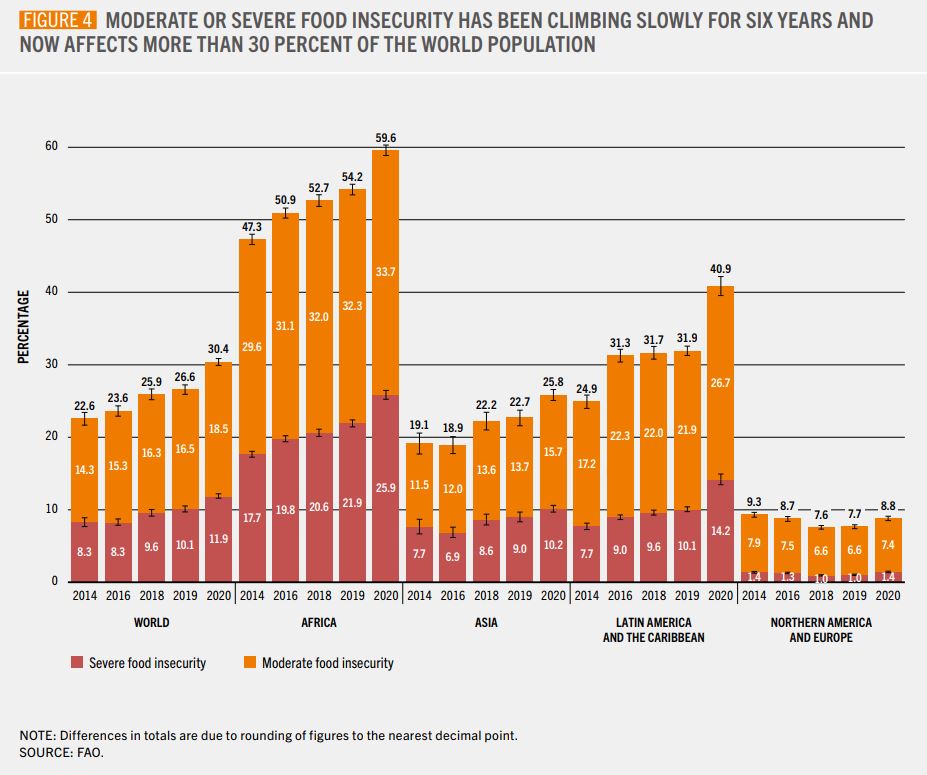

5. Severe food insecurity has been on the rise, and now accounts for at least 30 percent of the world population

6. Violent conflict is increasing

By 2020, military spending had risen to its highest level since before the end of the Cold War, as had the international trade in major weapons.

Emerging and recovering from violent conflict can take decades. Violence continues in Afghanistan, which now has the second-highest number of people in emergency food insecurity in the world. Although Somalia gradually recovered from food insecurity and famine in 2011, food insecurity is worsening once again, and more than half a million people are on the brink of famine, in large part owing to conflict.

7. As a proportion of regional population, the scale across Asia, Latin America and Africa remains staggering

8. Women continue to bear the brunt of the gender gap in food security across all regions - this time by 10 percent more than men in 2020

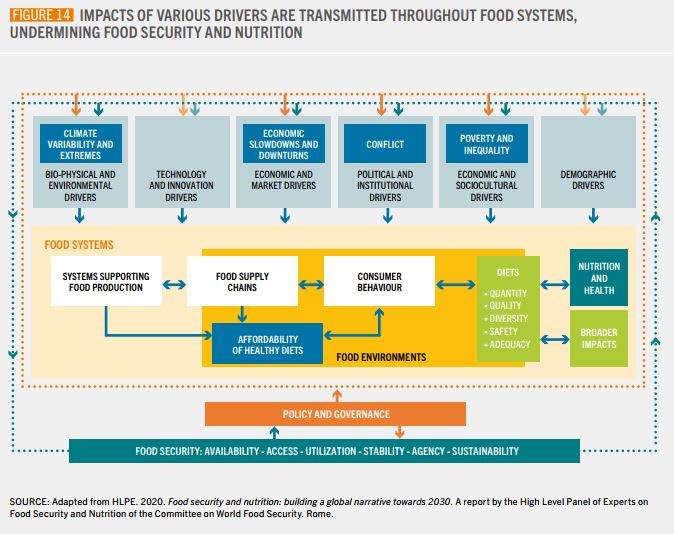

9. Transforming our global food system is not an academic exercise. It is essential

Because food systems are also social systems and reflect the inequalities found in all societies, food security is vulnerable to challenges ranging from pandemics to violence.

We live in a world of challenges and shocks, and our food systems must be built to withstand and recover from these challenges in ways that deliver food and nutrition security for all people. Hunger and malnutrition do not continue for want of solutions, but rather for want of the political will and resources to implement the solutions at hand and to respect, protect, and fulfill the right to food.” – Global Hunger Index 2021

10. Conflict, climate extremes and economic slowdowns are key drivers in increasing the prevalence of undernourishment (PoU)

11. Conflict is the number 1 driver of food insecurity in 2020, on its own and combined with other drivers

12. Hunger is higher and has increased since 2010 in countries affected by key 'drivers', than those that have not faced conflict, climate shocks or economic slowdowns

13. Conflict is devastating for children, driving up undernutrition and child mortality

14. The world is not on track to achieve the goal of Zero Hunger by 2030 and past gains have been built on an unsustainable foundation

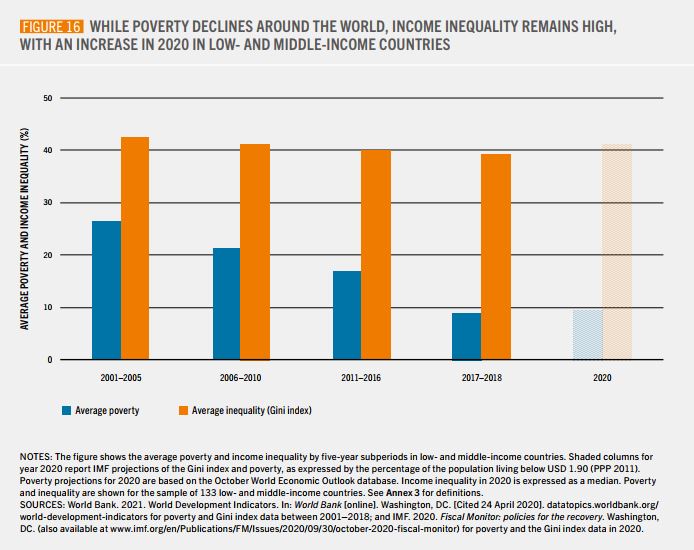

15. Income inequality remains high, and is increasing in low and middle-income countries.

For the first time in more than 20 years (taking into account Philip Alston’s criticisms of measuring poverty), poverty and income inequality at the global level increased in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the measures put in place to contain it.

The number of “new poor” (i.e. in addition to the number of people who were already poor), resulting from the pandemic was estimated by The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021 report to be between 119 and 124 million in 2020. In 2021, this number is set to rise to between 143 and 163 million.

At the centre of these drivers and complex dynamics affecting the state of global hunger, income inequality grew during the pandemic, which increased from 38 to 41 percent in 2020.

This feature has been developed as part of the World Food Day 2021 educational partnership by developmenteducation.ie and Scoilnet